In March 2023, we uncovered a previously unknown APT campaign in the region of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict that involved the use of PowerMagic and CommonMagic implants. However, at the time it was not clear which threat actor was behind the attack. Since the release of our report about CommonMagic, we have been looking for additional clues that would allow us to learn more about this actor. As we expected, we have been able to gain a deeper insight into the “bad magic” story.

While looking for implants bearing similarities with PowerMagic and CommonMagic, we identified a cluster of even more sophisticated malicious activities originating from the same threat actor. What was most interesting about it is that its victims were located not only in the Donetsk, Lugansk and Crimea regions, but also in central and western Ukraine. Targets included individuals, as well as diplomatic and research organizations. The newly discovered campaign involved using a modular framework we dubbed CloudWizard. Its features include taking screenshots, microphone recording, keylogging and more.

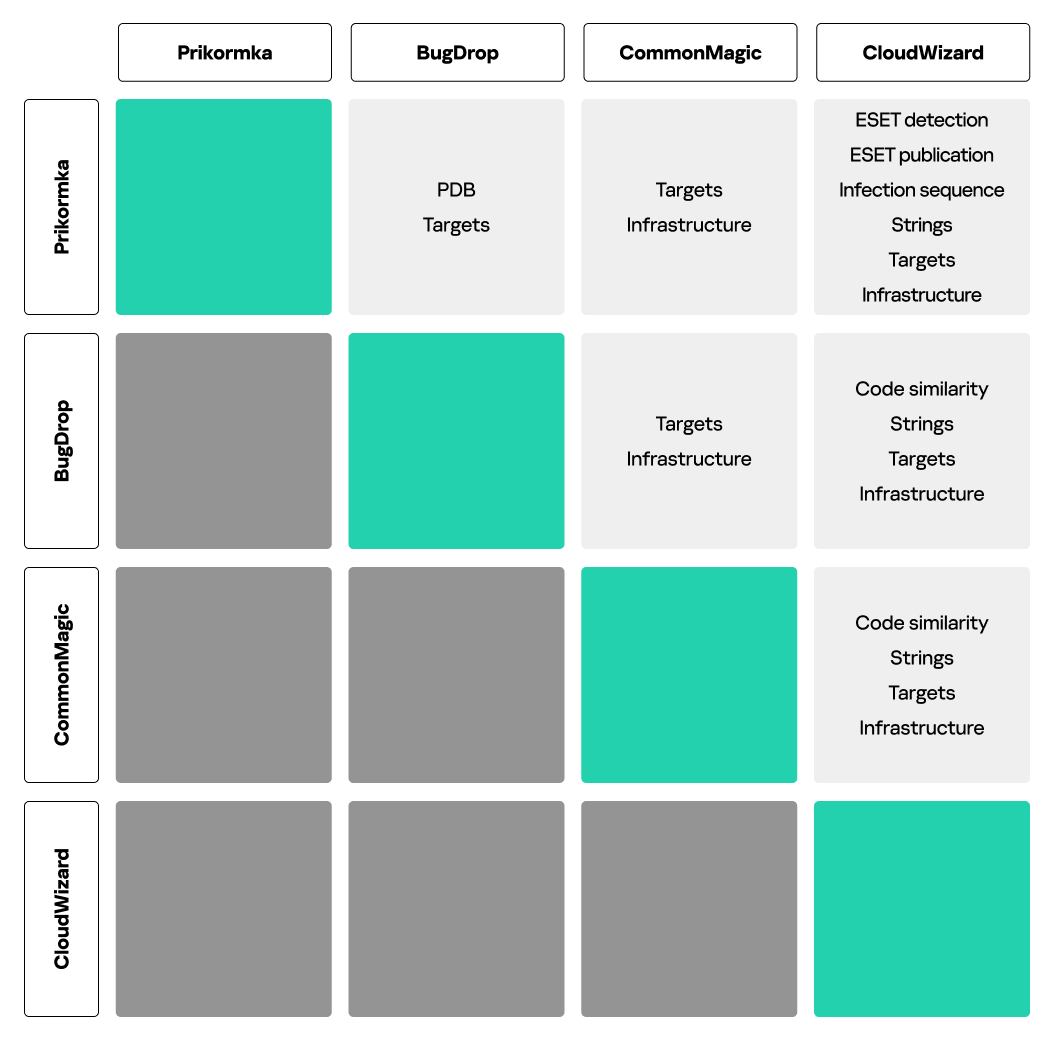

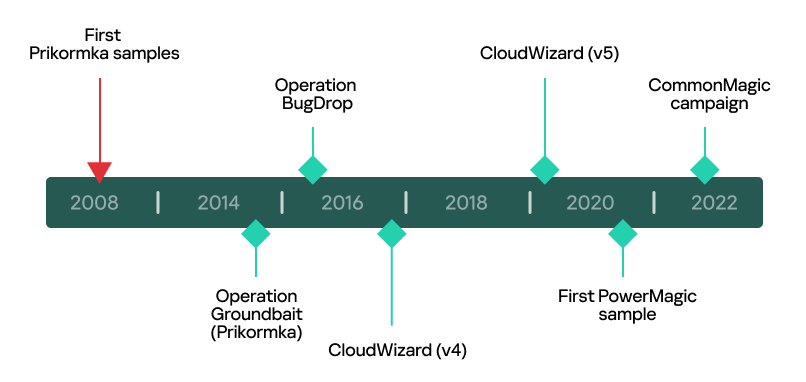

Over the years, the infosec community has discovered multiple APTs operating in the Russo-Ukrainian conflict region – Gamaredon, CloudAtlas, BlackEnergy and many others. Some of these APTs have long been forgotten in the past – such as Prikormka (Operation Groundbait), discovered by ESET in 2016. While there have been no updates about Prikormka or Operation Groundbait for a few years now, we discovered multiple similarities between the malware used in that campaign, CommonMagic and CloudWizard. Upon further investigation, we found that CloudWizard has a rich and interesting history that we decided to dig into. Our findings we also shared on the cybersecurity conference Positive Hack Days. You can watch our presentation here.

Initial findings

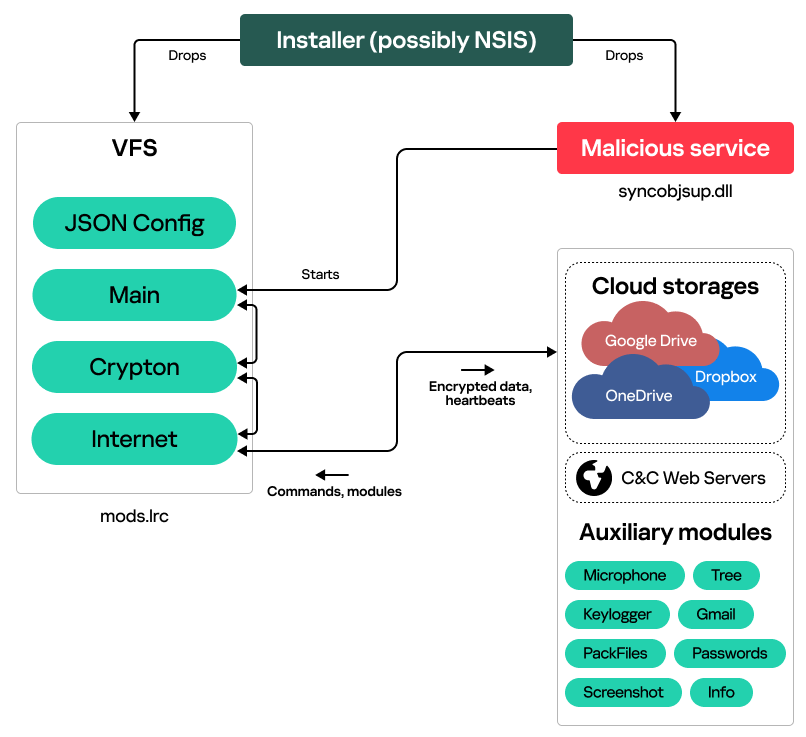

Our investigation started with telemetry data coming from an active infection, with malware running as a suspicious Windows service named “syncobjsup”. This service was controlled by a DLL with an equally suspicious path “C:\ProgramData\Apparition Storage\syncobjsup.dll”. Upon execution, we found this DLL to decrypt data from the file mods.lrc that is located in the same directory as the DLL. The cipher used for decryption was RC5, with the key 88 6A 3F 24 D3 08 A3 85 E6 21 28 45 77 13 D0 38. However, decryption of the file with the standard RC5 implementation yielded only junk data. A closer look into the RC5 implementation in the sample revealed that it was faulty:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

for (i = 0; i < 4; i += 2) { A = buf[i]; B = buf[i + 1]; for (j = 12; j > 0; --j) { v2 = rotate_right(B - S[2 * i + 1], A); B = A ^ v2; A ^= v2 ^ rotate_right(A - S[2 * i], A ^ v2); } } |

The bug is in the inner loop: it uses the variable i instead of j.

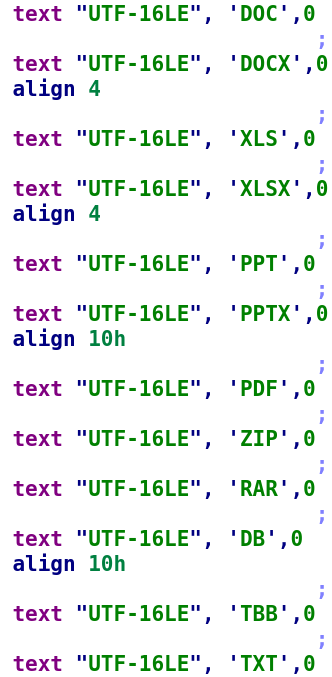

A search for this incorrect implementation revealed a GitHub gist of the code that has been likely borrowed by the implant’s developers. In the comments to this gist, GitHub users highlight the error:

What is also interesting is that the key from the gist is the same as the one used in the syncobjsup.dll library.

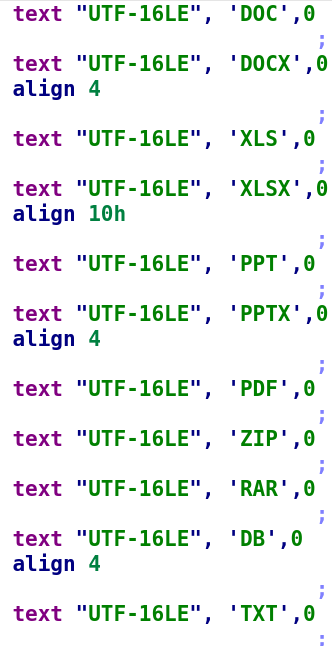

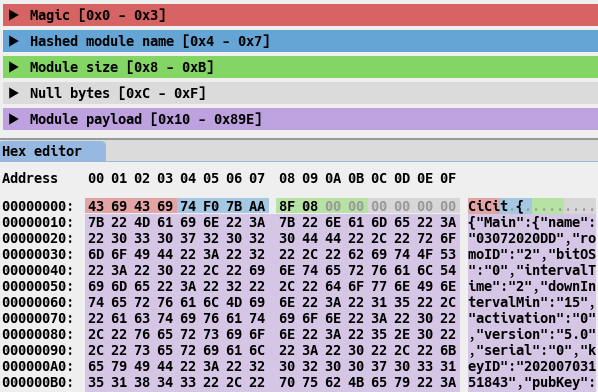

The decrypted file looked to us like a virtual file system (VFS), containing multiple executables and their JSON-encoded configurations:

Each entry in this VFS contains magic bytes (‘CiCi’), a ROR6 hash of the entry name, as well as the entry size and contents.

Inside mods.lrc, we found:

- Three DLLs (with export table names Main.dll, Crypton.dll and Internet.dll);

- A JSON configuration of these DLLs.

The syncobjsup.dll DLL iterates over VFS entries, looking for an entry with the name “Main” (ROR6 hash: 0xAA23406F). This entry contains CloudWizard’s Main.dll orchestrator library, which is reflectively loaded and launched by invoking its SvcEntry export.

Digging into the orchestrator

Upon launching, the orchestrator spawns a suspended WmiPrvSE.exe process and injects itself into it. From the WmiPrvSE.exe process, it makes a backup of the VFS file, copying mods.lrc to mods.lrs. It then parses mods.lrs to obtain all the framework module DLLs and their configurations. As mentioned above, configurations are JSON files with dictionary objects:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

{ "Screenshot": { "type": "3", "intervalSec": "4", "numberPack": "24", "winTitle": [ "SKYPE", "VIBER" ] }, "Keylogger": { "bufSize": "100" }, "Microphone": { "intervalSec": "500", "acousticStart": "1" } } |

The orchestrator itself contains a configuration with parameters such as:

- Victim ID (e.g., 03072020DD);

- Framework version (latest observed version is 5.0);

- Interval between two consecutive heartbeats.

After launching modules, the orchestrator starts communicating with the attackers by sending heartbeat messages. Each heartbeat is a JSON file with victim information and a list of loaded modules:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

{ "name": "<victim_id>", "romoID": "2", "bitOS": "64", "version": "5.0", "serial": "<infection_timestamp>", "keyID": "<key_id>", "ip": "0.0.0.0", "state": [ "Main","Crypton","Internet","Screenshot", "USB","Keylogger","Gmail" ], "state2": [ {"Module": "Main","time_mode": "2","Version": "4.7"}, {"Module": "Crypton","time_mode": "2","Version": "1.0"}, {"Module": "Internet","time_mode": "2","Version": "0.07"}, {"Module": "Screenshot","time_mode": "2","Version": "0.01"}, {"Module": "USB","time_mode": "2","Version": "0.01"}, {"Module": "Keylogger","time_mode": "2","Version": "0.01"}, {"Module": "Gmail","time_mode": "2","Version": "0.06"} ] } |

This JSON string is encrypted with the cryptography module (Crypton.dll from the VFS) and sent to the attackers with the internet communication module (Internet.dll).

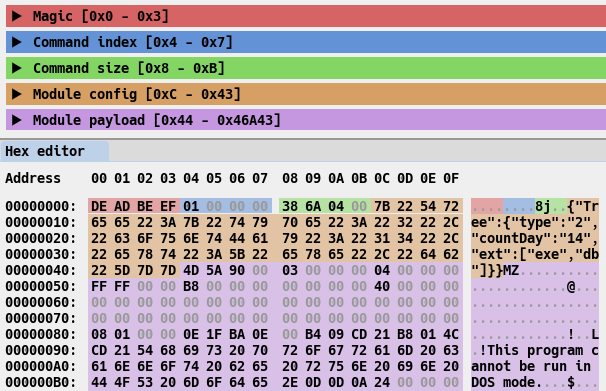

In response to the heartbeats, the orchestrator receives commands allowing it to perform module management: install, start, stop, delete modules or change their configurations. Each command contains magic bytes (DE AD BE EF) and a JSON string (e.g., {"Delete": ["Keylogger", "Screenshot"]}), optionally followed by a module DLL file.

Encryption and communication

As we have mentioned above, two modules (Crypton.dll and Internet.dll) are bundled with every installation of the CloudWizard framework. The Crypton module performs encryption and decryption of all communications. It uses two encryption algorithms:

- Heartbeat messages and commands are encrypted with AES (the key is specified in the JSON configuration VFS file)

- Other data (e.g., module execution results) is encrypted with a combination of AES and RSA. First, the data is encrypted with a generated pseudorandom AES session key, and then the AES key is encrypted with RSA.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

if ( buffers->results.lenstr && buffers->results.str ) { v10 = RSA_Encrypt(AES_KEY, 32, &v8, &v7, pubKey, pubKeySize); if (v10) { free(v8); return v10; } v10 = AES_Encrypt(buffers->results.str, buffers->results.lenstr, &v4, &v6, AES_KEY); if (v10) goto LABEL_11; } if (buffers->state.lenstr && buffers->state.str) { v10 = AES_Encrypt(buffers->state.str, buffers->state.lenstr, &v3, &v5, phpKey); if (v10) goto LABEL_11; } |

- Cloud storages: OneDrive, Dropbox, Google Drive

- Web-based C2 server

The primary cloud storage is OneDrive, while Dropbox and Google Drive are used if OneDrive becomes inaccessible. The module’s configuration includes OAuth tokens required for cloud storage authentication.

As for the web server endpoint, it is used when the module can’t access any of the three cloud storages. To interact with it, it makes a GET request to the URL specified in its configuration, getting new commands in response. These commands likely include new cloud storage tokens.

While examining the strings of the network module, we found a string containing the directory name from the developer’s machine: D:\Projects\Work_2020\Soft_Version_5\Refactoring.

Module arsenal

Information gathering is performed through auxiliary DLL modules that have the following exported functions:

| Export function | Description |

| Start | Starts the module |

| Stop | Stops the module |

| Whoami | Returns JSON-object with information about module (e.g., {"Module":"Keylogger ","time_mode":"2","Version":"0.01"}).The time_mode value indicates whether the module is persistent (1 – no, 2 – yes). |

| GetResult | Returns results of module execution (e.g. collected screenshots, microphone recordings, etc.). Most modules return results in the form of ZIP archives (that are stored in memory) |

| GetSettings | Returns module configuration |

Modules can persist upon reboot (in this case they are saved in the mods.lrs VFS file) or executed in memory until the machine is shut down or the module is deleted by the operator.

In total, we found nine auxiliary modules performing different malicious activities such as file gathering, keylogging, taking screenshots, recording the microphone and stealing passwords.

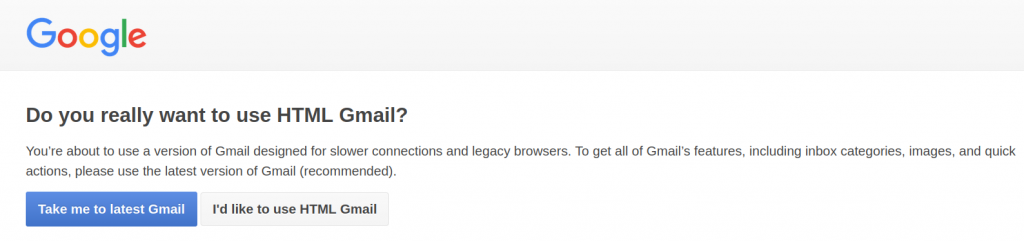

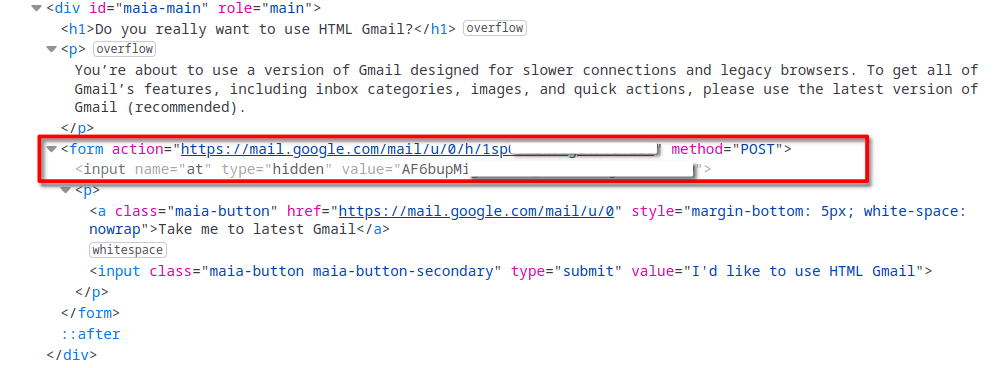

The module that looked most interesting to us is the one that performs email exfiltration from Gmail accounts. In order to steal, it reads Gmail cookies from browser databases. Then, it uses the obtained cookies to access the Gmail web interface in legacy mode by making a GET request to https://mail.google.com/mail/u/<account ID>/?ui=html&zy=h. When legacy mode is accessed for the first time, Gmail prompts the user to confirm whether they really wants to switch to legacy mode, sending the following webpage in response:

If the module receives such a prompt, it simulates a click on the “I’d like to use HTML Gmail” button by making a POST request to a URL from the prompt’s HTML code.

Having obtained access to the legacy web client, the module exfiltrates activity logs, the contact list and all the email messages.

What’s also interesting is that the code for this module was partially borrowed from the leaked Hacking Team source code.

Back to 2017

After obtaining the CloudWizard’s orchestrator and its modules, we were still missing one part of the infection chain: the framework installer. While searching through older telemetry data, we were able to identify multiple installers that were used from 2017 to 2020. The version of the implant installed at that time was 4.0 (as we wrote above, the most recent version we observed is 5.0).

The uncovered installer is built with NSIS. When launched, it drops three files:

- C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\WwanSvc\WinSubSvc.exe

- C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\MF\Depending.GRL (in other versions of the installer, this file is also placed under C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\MF\etwdrv.dll)

- C:\ProgramData\System\Vault\etwupd.dfg

Afterwards, it creates a service called “Windows Subsystem Service” that is configured to run the WinSubSvc.exe binary on every startup.

It is worth noting that the installer displays a message with the text “Well done!” after infection:

This may indicate that the installer we discovered is used to deploy CloudWizard via physical access to target machines, or that the installer attempts to mimic a Network Settings (as displayed in the window title) configurator.

The old (4.0) and new (5.0) CloudWizard versions have major differences, as outlined in the table below:

| Version 4.0 | Version 5.0 |

| Network communication and cryptography modules are contained within the main module | Network communication and cryptography modules are separate from each other |

| Framework source file compilation directory: D:\Projects\Work_2020\Soft_Version_4\Service | Framework source file compilation directory: D:\Projects\Work_2020\Soft_Version_5\Refactoring |

| Uses RC5 (hard-coded key: 7Ni9VnCs976Y5U4j) from the RC5Simple library for C2 server traffic encryption and decryption | Uses RSA and AES for C2 server traffic encryption and decryption (the keys are specified in a configuration file) |

Attribution magic

After spending considerable time researching CloudWizard, we decided to look for clues that would allow us to attribute it to an already known actor. CloudWizard reminded us of two campaigns observed in Ukraine and reported in public: Operation Groundbait and Operation BugDrop. Operation Groundbait was first described by ESET in 2016, with the first implants observed in 2008. While investigating Operation Groundbait, ESET uncovered the Prikormka malware, which is “the first publicly known Ukrainian malware that is being used in targeted attacks”. According to ESET’s report, the threat actors behind Operation Groundbait “most likely operate from within Ukraine”.

As for Operation BugDrop, it is a campaign discovered by CyberX in 2017. In their report, CyberX claims (without providing strong evidence) that Operation BugDrop has similarities with Operation Groundbait. And indeed, we have discovered evidence confirming this:

- Prikormka USB DOCS_STEALER module (MD5: 7275A6ED8EE314600A9B93038876F853B957B316) contains the PDB path D:\My\Projects_All\2015\wallex\iomus1_gz\Release\iomus.pdb;

- BugDrop USB stealer module (MD5: a2c27e73bc5dec88884e9c165e9372c9) contains the PDB path D:\My\Projects_All\2016\iomus0_gz\Release\usdlg.pdb.

The following facts allow us to conclude with medium to high confidence that the CloudWizard framework is operated by the actor behind Operation Groundbait and Operation BugDrop:

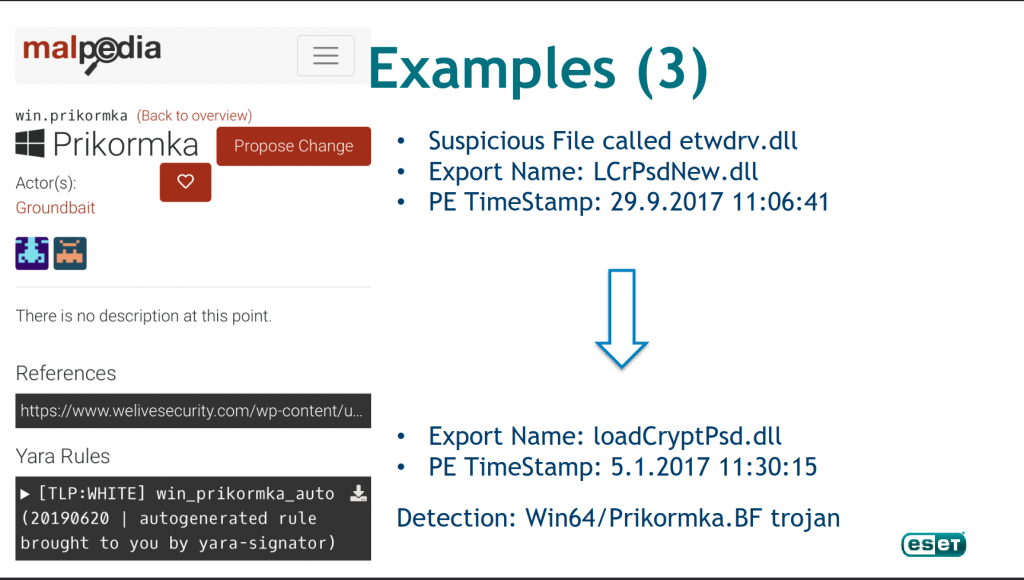

- ESET researchers found the loader of CloudWizard version 4.0 dll (with the export name LCrPsdNew.dll) to be similar to a Prikormka DLL. The similarity between these two files has been noted in the Virus Bulletin 2019 talk ‘Rich headers: leveraging the mysterious artifact of the PE format’ (slide 42)

Slide 42 of the VB2019 ‘Rich headers: leveraging the mysterious artifact of the PE format’ talk

- ESET detects a loader of a CloudWizard v. 4 sample (MD5: 406494bf3cabbd34ff56dcbeec46f5d6, PDB path: D:\Projects\Work_2017\Service\Interactive Service_system\Release\Service.pdb) as Win32/Prikormka.CQ.

- According to our telemetry data, multiple infections with the Prikormka malware ended with a subsequent infection with the CloudWizard framework

- Implementation of several modules of CloudWizard resembles the corresponding one from the Prikormka and BugDrop modules, though rewritten from C to C++:

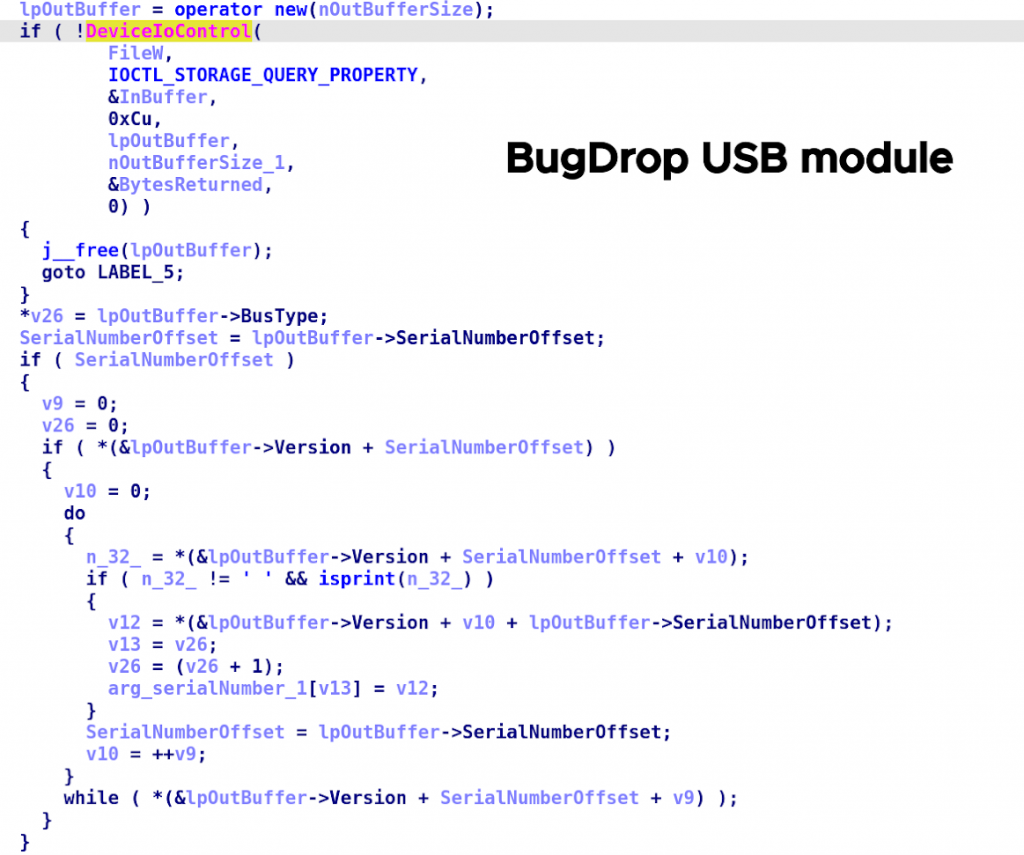

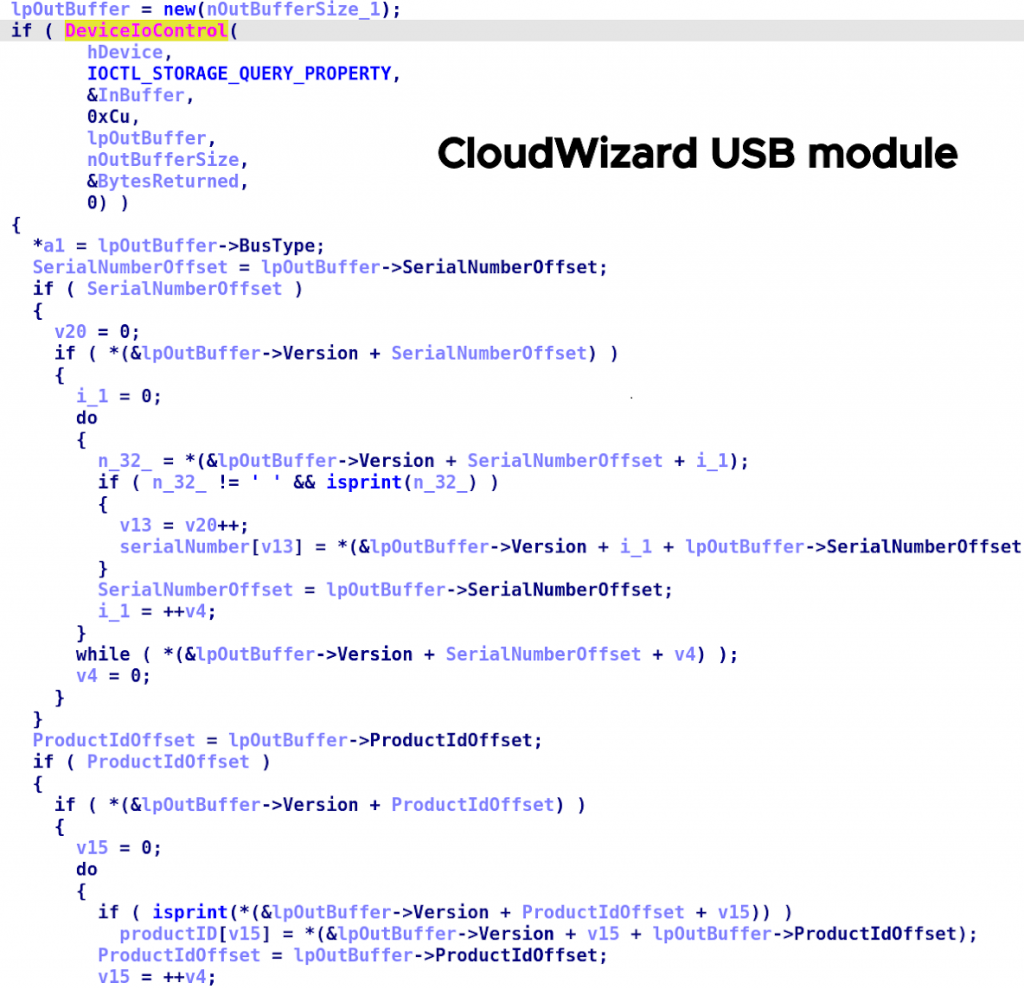

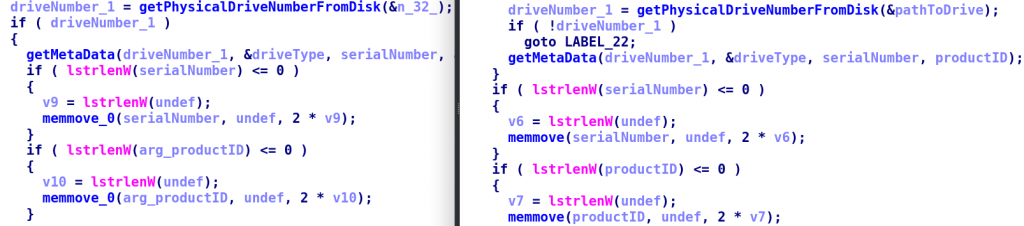

- USB stealer modules retrieve the serial numbers and product IDs of connected USB devices via the IOCTL_STORAGE_QUERY_PROPERTY system call. The default fallback value in case of failure is the same, “undef”.

Retrieval of USB device serial number and product ID in BugDrop (MD5: F8BDE730EA3843441A657A103E90985E)

Retrieval of USB device serial number and product ID in CloudWizard (MD5: 39B01A6A025F672085835BD699762AEC)

Assignment of the ‘undef’ string in BugDrop (left) and CloudWizard (right) in the samples above

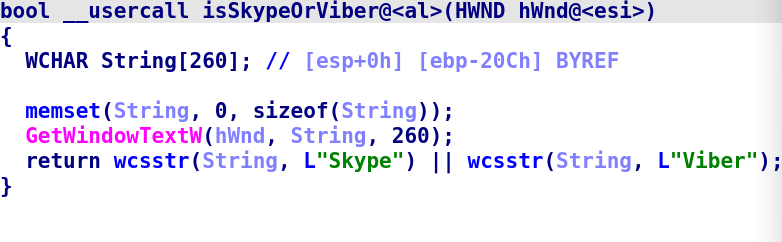

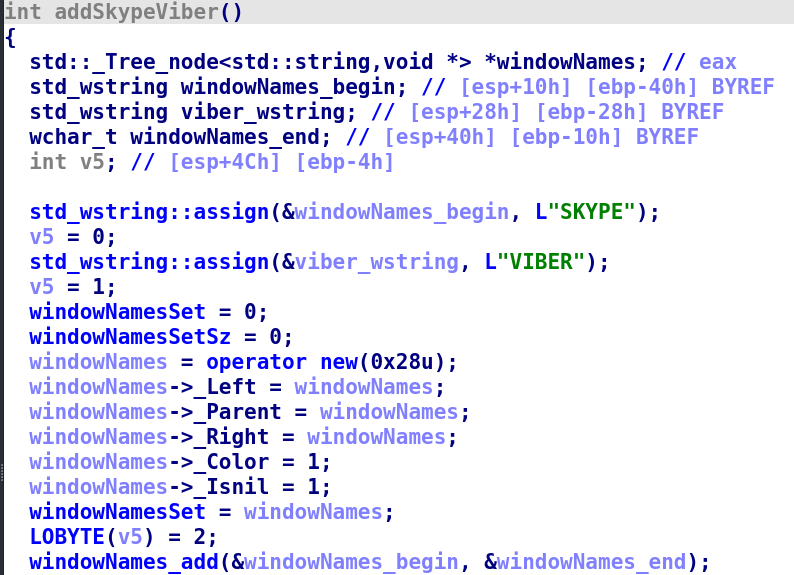

- The modules for taking screenshots use the same list of window names that trigger an increase in the frequency of screenshot taking: ‘Skype’ and ‘Viber’. CloudWizard and Prikormka share the same default value for the screenshot taking interval (15 minutes).

Comparison of the window title text in Prikormka (MD5: 16793D6C3F2D56708E5FC68C883805B5)

Addition of the ‘SKYPE’ and ‘VIBER’ string to a set of window titles in CloudWizard (MD5: 26E55D10020FBC75D80589C081782EA2)

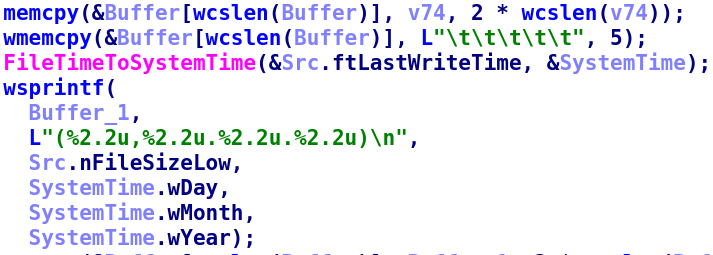

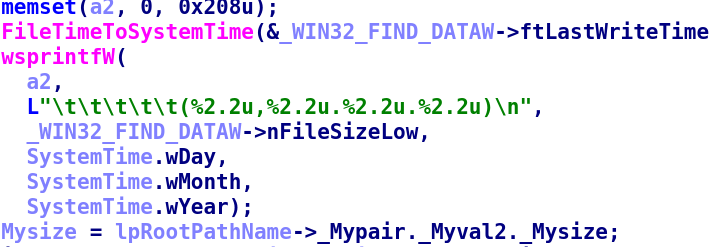

- The file listing modules in both Prikormka and CloudWizard samples have the same name: Tree. They also use the same format string for directory listings: “\t\t\t\t\t(%2.2u,%2.2u.%2.2u.%2.2u)\n”.

Use of the same format string for directory listings in Prikormka (above, MD5: EB56F9F7692F933BEE9660DFDFABAE3A) and CloudWizard (below, MD5: BFF64B896B5253B5870FE61221D9934D)

- Microphone modules record sound in the same way: first making a WAV recording using Windows Multimedia API and then converting it to MP3 using the LAME library. While this pattern is common in malware, the strings used to specify settings for the LAME library are specific: 8000 Hz and 16 Kbps. Both Prikormka and CloudWizard modules extract integers from these strings, using them in the LAME library.

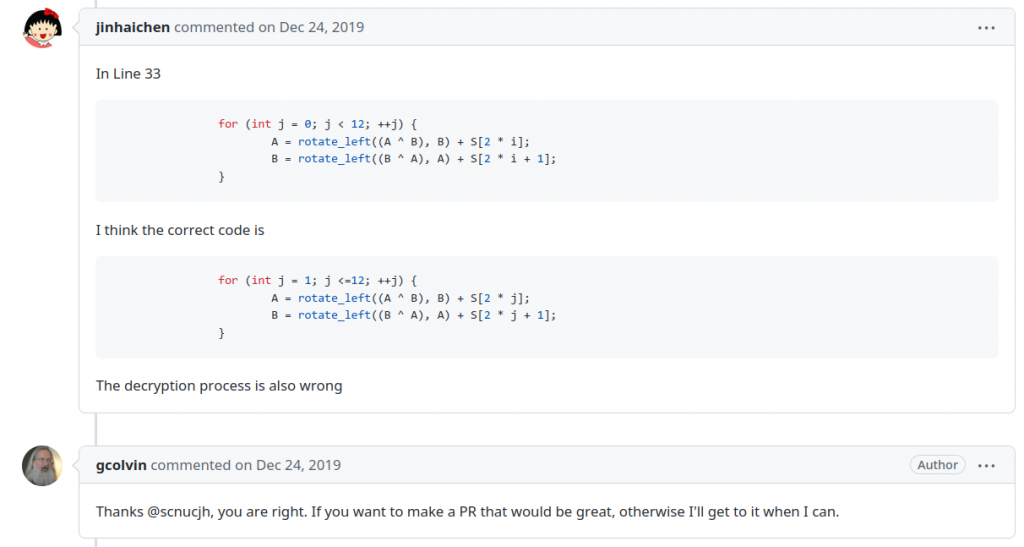

- A similar order of extensions is used in extension lists found in Prikormka and CloudWizard modules:

Extension lists in Prikormka (left, MD5: EB56F9F7692F933BEE9660DFDFABAE3A) and CloudWizard (right, MD5: BFF64B896B5253B5870FE61221D9934D)

- USB stealer modules retrieve the serial numbers and product IDs of connected USB devices via the IOCTL_STORAGE_QUERY_PROPERTY system call. The default fallback value in case of failure is the same, “undef”.

- In Prikormka, the names of files to be uploaded to the C2 server have the name format mm.yy_hh.mm.ss.<extension>. In CloudWizard, the files have the name format dd.mm.yyyy_hh.mm.ss.ms.dat. The date substituted into the name format strings is retrieved from the GetLocalTime API function.

- The C2 servers of both Prikormka and CloudWizard are hosted by Ukrainian hosting services. Additionally, there are similarities between BugDrop and CloudWizard in terms of exfiltrating files to the Dropbox cloud storage.

- Victims of Prikormka, BugDrop and CloudWizard are located in western and central Ukraine, as well as the area of conflict in Eastern Europe.

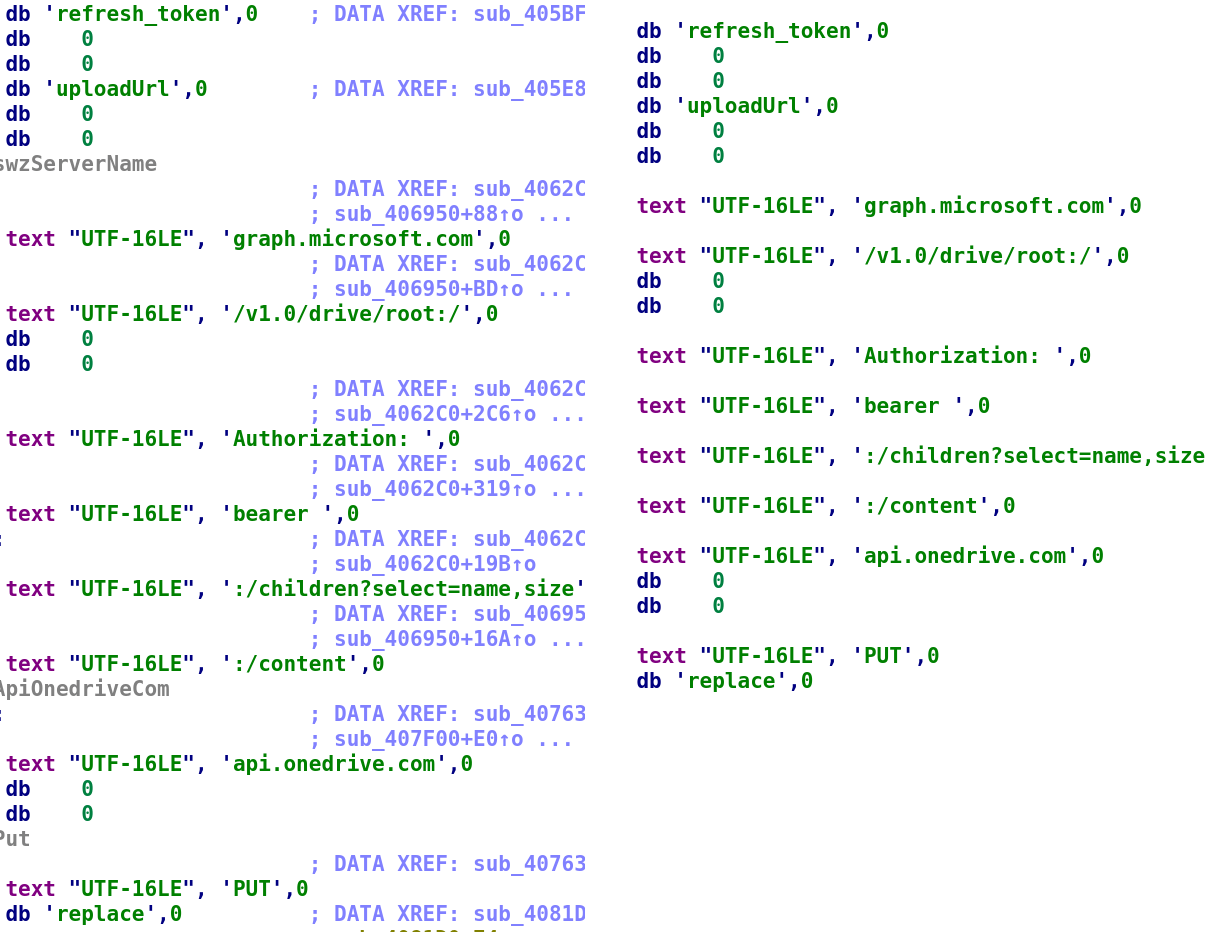

As for the similarities between CloudWizard and CommonMagic, they are as follows:

- The code that performs communication with OneDrive is identical in both frameworks. We did not find this code to be part of any open-source library. This code uses the same user agent: “Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/42.0.2311.135 Safari/537.36 Edge/12.10136”.

The same strings in the internet communication module of CloudWizard (left, MD5: 84BDB1DC4B037F9A46C001764C115A32) and CommonMagic (right, MD5: 7C0E5627FD25C40374BC22035D3FADD8)

- Both frameworks, CloudWizard (version 4) and CommonMagic use the RC5Simple library for encryption. Files encrypted with RC5Simple start with a 7-byte header, which is set to ‘RC5SIMP’ in the library source code. However, this value has been changed in the malicious implants: DUREX43 in CloudWizard and Hwo7X8p in CommonMagic. Additionally, CloudWizard and CommonMagic use the RapidJSON library for parsing JSON objects.

- Names of files uploaded to the C2 server in CommonMagic have the format mm.dd _hh.mm.ss.ms.dat (in CloudWizard, the name format is dd.mm.yyyy_hh.mm.ss.ms.dat).

- Victim IDs extracted from CloudWizard and CommonMagic samples are similar: they contain a date followed by the two same letters, e.g. 03072020DD, 05082020BB in CloudWizard and WorkObj20220729FF in CommonMagic.

- Victims of CommonMagic and CloudWizard are located in the area of conflict in Eastern Europe.

So what?

We initiated our investigation back in 2022, starting with simple malicious PowerShell scripts deployed by an unknown actor and ended up discovering and attributing two large related modular frameworks: CommonMagic and CloudWizard. As our research demonstrates, their origins date back to 2008, the year the first Prikormka samples were discovered. Since 2017, there have been no traces of Groundbait and BugDrop operations. However, the actor behind these two operations has not ceased their activity, and has continued developing their cyberespionage toolset and infecting targets of interest for more than 15 years.

Indicators of compromise

NSIS installer

MD5 0edd23bbea61467f144d14df2a5a043e

SHA256 177f1216b55058e30a3ce319dc1c7a9b1e1579ea3d009ba965b18f795c1071a4

Loader (syncobjsup.dll)

MD5 a2050f83ba2aa1c4c95567a5ee155dca

SHA256 041e4dcdc0c7eea5740a65c3a15b51ed0e1f0ebd6ba820e2c4cd8fa34fb891a2

Orchestrator (Main.dll)

MD5 0ca329fe3d99acfaf209cea559994608

SHA256 11012717a77fe491d91174969486fbaa3d3e2ec7c8d543f9572809b5cf0f2119

Domains and IPs

CloudWizard APT: the bad magic story goes on