Mobile dropper Trojans are one of today’s most rapidly growing classes of malware. In Q1 2019, droppers are in the 2nd or 3rd position in terms of share of total detected threats, while holding nearly half of all Top 20 places in 2018. Since the droppers’ main task is to deliver payload while sidestepping the protective barriers, and their developers are fully bent on countering detection, this is probably one of the most dangerous classes of malware.

One of the most dangerous and widely spread families of Trojan droppers is Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar. Originally created as a MaaS infrastructure, today Hqwar is used for both small-scale attacks and big ones affecting thousands of users all over the world.

The very first versions of Hqwar saw the light in early 2016, getting quite popular by the end of the same year. It peaked in Q3 2018, when substantial numbers of financial malware payloads would come “packaged” with this dropper. Yet, beginning Q4 2018, we observe its decline. The likely reason is the tool is not updated frequently enough by its author, causing a customer outflow.

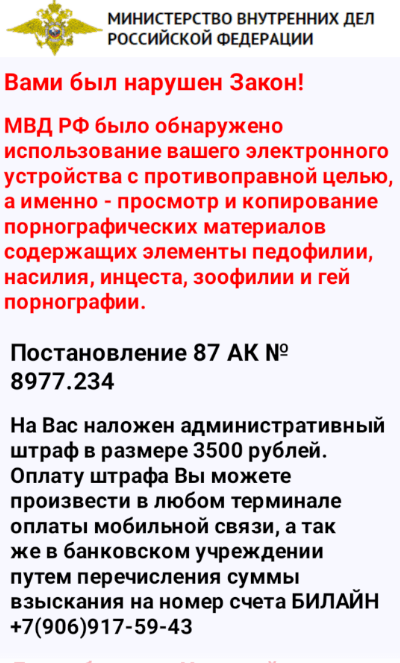

The very first Trojan packed with Hqwar was a piece of ransomware targeting Russian users. This is how this disgrace introduced itself to the victims, impersonating the Ministry of Internal Affairs (note that Hqwar was built by a Russian-speaking author, and many of its clients prey on Russian users):

Now one can say that only the lazy did not use Hqwar: Kaspersky’s collection of viruses features over 200,000 Trojans packed using Hqwar. When decrypting and unpacking these malicious objects, we found that almost 80% of them are financial threats, while nearly one third represent the banking Trojan family of Faketoken. In fact, it was the first ever banking Trojan whose authors began using Hqwar.

The Top 10 list of payloads most often bundled with Hqwar features such widely distributed Trojans as Asacub, Marcher and Svpeng. On several occasions, the dropper was carrying Korean bankers of the Wroba family and such famous SMS Trojans as Opfake and Fakeinst. But their authors seem to have used Hqwar just to try things out, so to speak: these “matryoshkas” did not gain much popularity. All in all, we know of 22 families of different Trojans packed with Hqwar, which shows how much interest cybercriminals take in droppers.

| Family | %* | |

| 1 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Faketoken | 28.81% |

| 2 | HEUR:Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr | 14.53% |

| 3 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub | 10.10% |

| 4 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Marcher | 8.44% |

| 5 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Grapereh | 7.67% |

| 6 | HEUR:Trojan-Spy.AndroidOS.SmsThief | 7.20% |

| 7 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Gugi | 6.18% |

| 8 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Svpeng | 5.38% |

| 9 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent | 5.24% |

| 10 | HEUR:Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Palp | 1.97% |

* percentage of all unpacked objects

What’s inside

From the technical viewpoint, the dropper is a wrapper around the payload’s DEX file to be decrypted and loaded, comprising two classes.

If we are to simplify and forget about obfuscation, the dropper’s workflow can be presented as follows:

- open a file from assets;

- decrypt it using RC4 and a hardwired key;

- delegate control with the help of DexClas`sLoader LoadClass.

Everything the unpacked Trojan needs to operate is in the dropper’s APK file: all activity, receiver and service records are written down in the manifest, the pictures are where they should be (with unique names generated for all objects). As Hqwar doesn’t “drop” the APK file but only loads the code, there is no need for an app installation request which can potentially be declined by the user (however, this approach is not exactly good for persistency: once the dropper is deleted by the user, the Trojan is deleted, too). The main Trojan’s body is obfuscated, so the original malware cannot be recognized.

Interesting fact: for some time Hqwar had co-existed with a Trojan called Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Fakeinst.hq, with which it had quite a few things in common:

- The two used similar line obfuscation methods (it might be that the authors of both had used a ready-made decryption algorithm).

- A setup was used in which a portion of code was loaded from AES-encrypted asset files. It is worth noting that in Fakeinst.hq one of the encrypted files was an APK file, while the other one was a DEX file used to install a secondary APK (payload). This made for a triple matryoshka: the original dropper at level one, an encrypted DEX file at level two, and an encrypted APK at three. This was done to preserve infection after the dropper itself was deleted. Broadly speaking, the trick is not new, but unlike other similar occasions, Hqwar and Fakeinst.hq used encrypted files with the same extension – DAT.

- In both cases, a similar certificate generation pattern was used:

This evidence proves nothing, of course. But it can be assumed that the author of Hqwar had begun with Russian SMS Trojans, while at the same time working on the “wrapper” infrastructure.

Services

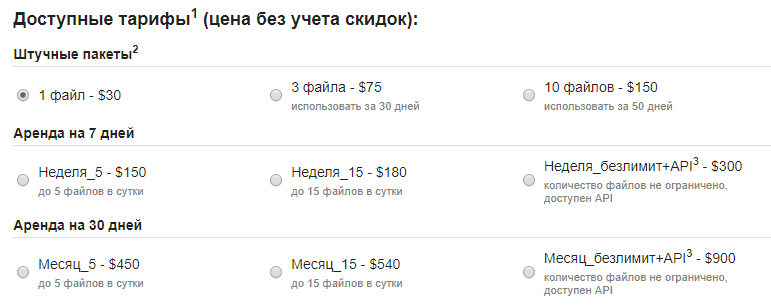

Hqwar owns its popularity to convenient infrastructure and pricing policy (as well as the fact that its maker is still at large and has no fear of being called to account for his actions).

An API exists to have the malware mass-produced. It is likely used by the makers of Trojans like Faketoken, Asacub, Marcher, etc.:

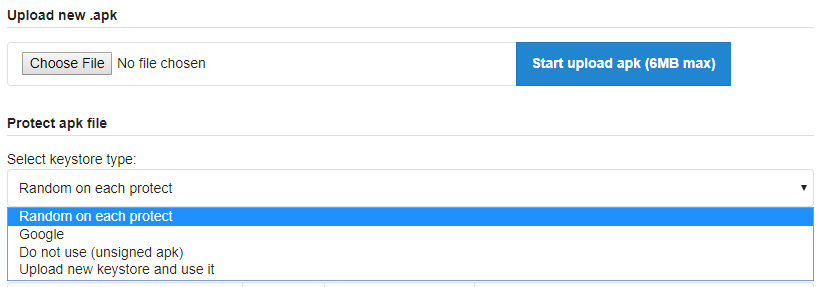

The need to have a certificate for each APK file is one of the places that could give one “a foothold” in Hqwar to reconstruct the certificate generation system. Therefore, the author has made it possible to load a random certificate – either stolen or from a legitimate application.

Conclusion

Despite all the convenient features the dropper’s author has built into it, we believe Hqwar (and similar wrappers) may soon lose much of their popularity: their counter-detection mechanisms have become obsolete, while the structure of the APK file implies there are places that cannot be “littered”, allowing for timely detection of threats (exactly what Kaspersky’s protective solutions are for).

IOC

8011659ab9b2e79230b4ccd7212758e97ac5152a

3cb8e3b699746ba578a7d387cf742bc558b47a2e

9c430147d9f0eca15db7ad1f4cd03ab3a976c549

8d777121b5b79de68d5e35a19e7f826bd7793531

6c9d0f50412175fc5f42c918aa99017f5f4d92a5

13e88a4c88ff76b1f7c3c3103fe3dac8fc06da6b

1f757946a6ca6e181bef4b4eafc54fb81a99efdf

bf81fc02d5aca759ffabd23be12b6c9da65da23a

fecdb304f5725b2b5da4d0fb141e57fbbeb5ebb8

f6def3411e6e599e769357cebe838f89053757b8

14083557d050b01d393e91f8850f614c965c5727

4d68516c9a19011e72fe0982dadd99cc1a7faf9b

fb4b166f42dfc36fdcc49ed0dde18bdc2a6774df

9f75a57eb3476bd545227bda8d54a4ad50c2c465

21b9e289f0a9eba65bb463cc8d624f1f9892aeac

c3090c9b31d0cc67661f526e9ea878af426fb8d9

e48113cedf180d427306b66b6f736ad66614202b

01f9b39c8228bd2cc68dd3d66c15c7388fbd755f

b6524f0c303a3323951af5e91d7cd1ac5f3b274f

81abbbbe81f89bb75ad97bf82c4d2c5571582191

332870d5f516e7f7e263b861939ed76d78bf0bff

4b9979205715c01035c966e5a94ab3842fb6f6a5

e66ef3bffa9cd0d3635a198b33e8b48f5454d96b

374a855e7bce7fb73ba7ce1305ae77089286a729

ed410ffad0a2f549a4ccc5c591b9115f71a8e345

9bff9215b8d2008d1282b5316be9cbd890321f3a

d13139e7c3f4de738ad7a58431d5ceea94920045

17ee7fbd871a384d7b596132999242b516dbdaa2

a01ae5c73693dad0fdf4ee69dbf03d9079a81c1c

c366eae7941754ecb29de453c40a2d9b15c91e7c

9b6adb0ce5c6e2ed364d802b286ab1a19c16747a

04026f896ba26374ff48ccf12d20110202e0f2a7

5c5ddc13cf02f30968f5f09b8dd7a3bedaa9ffdf

1f18595d6607f44c9ced44c091c027ab291198e4

bf33b37be16839708e6855a664459620c3cfda5f

ead2362be3fa1237f163dae5bfa8809f2d4692cf

f10f2c245843d9afc92f40be7cd83a4d2d2bb992

4e61161587eebb1a995bf1a3547fa194dab81872

f4ba07de1be13112532d5b24ab6dca1f9ca8068a

da8deed6054c55b23ec7201fb50ee1415e1cffc6

e7936d5b99777873a21f7874fc1efda98a568c3c

a656e7589b52bf38b70facd1afb585745b328ebe

8aeaa1e8efc72a8c156bad029e167b6dce1cd81b

de09f03c401141beb05f229515abb64811ddb853

18dce8f0b911847dc888404eb447eeae6b264fec

5f6447f9367bcb70fee946710961d027c3ae8d7e

e7023902d044e154fdf77f82d9605f2f24373d90

8c15c4873c4050bf55bbd9fbdf4ec04f5b94f90d

74f4ba7c065e6538bd95dc92f9a901171437a1c5

522aad03e29e3ada2fb95a9a0a960dc0aa73272b

HQWar: the higher it flies, the harder it drops

Claire Days

I have this. In my new android. Virus Total found it. Please help me.

Yuliya

Have you tried to find and remove it with Kaspersky Internet Security for Android?

https://www.kaspersky.com/android-security

Jack daniels

My samsung internet browser was detected android.hqwar.gen50116 by quickheal. Possible cause of infection?

Securelist

Hi Jack!

Quick Heal isn’t our product, so we cannot say neither what is the source of the infection nor whether it is an infection at all, and not a false positive. You can contact your security solution provider tech support team to ask why it detects your browser.