The InfoWatch analytical centre presents a summary of the past year’s internal IT-security incidents around the globe. The goal of this project is to analyze all confidential data leaks (including personal data leaks), reported by the media during the past year. We have analyzed leaks from around the world in all types of corporations.

The InfoWatch analytical centre started its leak database in 2004. As of today, the database contains records on several thousand leaks. The database served as the basis for this study.

The Source of Data Leaks

Last year, researchers agreed that there were no obvious geographical patterns regarding data leaks. This does not mean that such patterns do not exist, however. If most of the information about leaks is taken from the media, taking country of origin into account distorts the results significantly. Every country has its own media laws, its own rules and practices for keeping data confidential, not to mention language barrier problems. This is why country distribution was not included in the survey.

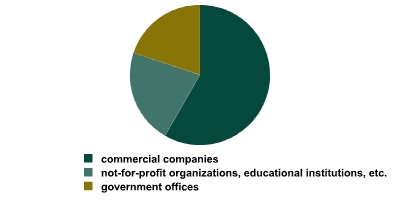

The following diagram represents a leak distribution based on organization type. Last year we divided organizations into government-based and private. This year, in addition to government offices and private corporations, we have included not-for-profit organizations (mostly educational institutions).

Leak distribution based on organization type.

The results of a similar InfoWatch study in 2006 were split at 34% for government offices and 66% for private organizations. In 2007, the share of government offices dropped to 22%. Since no data regarding a change in leak publication policies has been noted, it is logical to assume that government offices have increased their internal security measures.

In general, it is easier to introduce the required security measures in government offices, since it easier to bypass legal problems. This includes a general ban on the viewing of messages broadcast over communication channels that is present in most countries. The means to bypassing this ban are different for each country, yet it is obvious that such an act is easier for a government office to carry out.

Another reason for the drop in government data leaks is an increased awareness of the problems associated with protecting confidential data. The media and, as a result, the public are interested in publicizing all data leaks, including those that are unlikely to cause any harm, in addition to truly dangerous leaks that usually involve the government. The number of organizations processing confidential data has increased, and is made up of mostly non-governmental structures.

It is worth noting that the percentage of educational institutions in the study is rather large. On one hand, there is no strong commercial incentive to protect client data (students’ data, in this case); on the other hand, employee discipline in such institutions is considerably lower than that of public servants. Both of these factors make a drop in students’ data leaks in the near future highly unlikely.

The InfoWatch analytical department predicts an increase in the overall amount of data leaks over the next three years. The share of governmental leaks will continue to slowly decline due mostly to an increase in the amount of organizations that process personal data. The difference in security measures between the governmental and private sectors is negligible, and will remain so in the foreseeable future.

Nature of Leaks

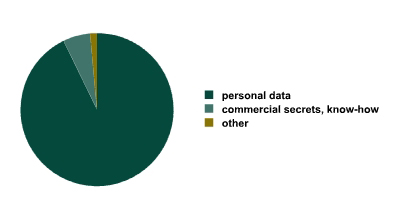

The following diagram represents a leak distribution based on data type. Commercial secrets and know-how are combined under one category, since they are classified as being the same in most countries (although know-how technically belongs to intellectual property in Russia – a new addition to Russian law). Moreover, such legal distinctions are often impossible to ascertain from a media analysis. The “other” category includes government secrets and situations where the data type is unknown.

Leak distribution based on the confidential data type.

In a similar InfoWatch study carried out in 2006, the personal data percentage was slightly lower (81%) as opposed to the current 93%. We believe that this increase goes beyond the statistical error margin and represents a real rise in personal data leaks. The value of personal data increases every year. As the economy becomes more and more “virtualised” and e-business develops, more and more ways to commit identity theft arise, hence the increase in the demand for personal data. The value of other types of confidential data is growing as well, but at a much lower rate than that of personal data.

A further increase in the value of personal data is expected, but it is unlikely that the overall number of leaks will increase, due to an increase in internal security measures.

Leakage Channels

Knowing possible data leakage channels is incredibly important for developing software-based and organizational security measures.

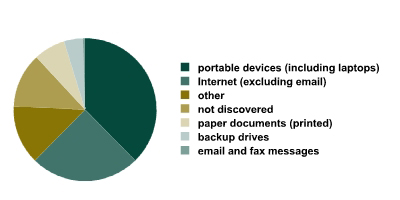

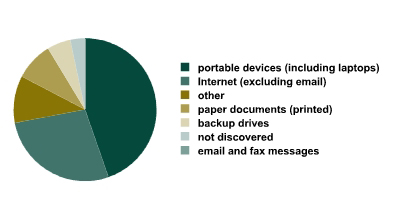

The following diagram represents a leak distribution based on the medium that was used to move the data outside the data system.

Leak distribution based on medium.

In comparison with 2006, the percentage of portable devices has decreased significantly (from 50% last year to 39% in 2007), while Internet channels have increased (from 12% last year to 25% in 2007). The percentages of other media are within the statistical margin of error, and are thus deemed unchanged. As the amount of leaks via the Internet increases, so does the need for online data leakage prevention systems.

It is interesting to note that last year only one case of an email-based leak was reported. One would presume that this channel is the most available and easiest to use. However, it is just as easy to control the email flow as it is to abuse it. In addition to serious anti-insider security systems, the market offers a vast array of primitive ways to protect email traffic. These are usually oriented on the messages themselves, since they are easy to view and archive. This acts as an obvious deterrent from using this channel to pass on confidential data. Sending confidential data via email by accident is also rather difficult.

When creating and integrating leak protection systems, it is important to note which leakage channels are currently the most “popular”.

If the aforementioned statistics are broken down into intentional and accidental leaks, we will see that both Internet and portable devices are the most popular channels for accidental data leaks. More often than not, it is a chance laptop theft (where the data is not intentionally targeted) or accidental file sharing. For intentional data theft, the most common channels are “other” and “undiscovered” (such as the theft of a desktop computer or a hard drive).

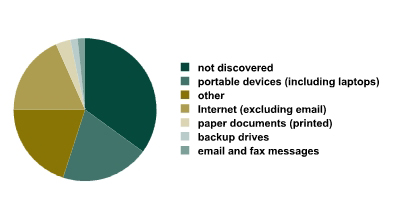

Leak distribution based on medium for intentional (top) and accidental (bottom) data leaks.

When integrating a data prevention system at an organization, the difference between the “intentional” and “accidental” statistics will be an important factor. For example, after installing an Internet traffic control system (the blue sectors: 27% accidental and 18% intentional), the system can prevent all 27% in the first case, but a lot less than 18% in the second. The malefactor`s actions are deliberate and often he knows about the prevention system. Therefore, he will try to use different channels that are not subject to control. Since the discrete use of such prevention systems is virtually impossible, the efficiency of preventing intentional data theft will be lower than for the same areas in the ‘accidental’ diagram.

Separating the intentional incidents from the accidental ones is straightforward. The only area that may cause problems is computer theft. Since we are looking specifically for data leaks, the demarcation is as follows. If the thief wanted to steal the data, then the theft is intentional. If he wanted to steal valuable hardware, then the data theft is secondary and is defined as accidental. Fortunately, the media almost always hints at the thief’s true intentions.

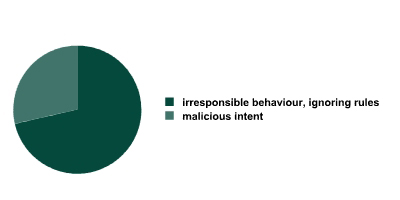

The following diagram shows the leak distribution according to intent.

Leak distribution based on intent.

The previous study had a similar distribution (77% and 23%). The difference between the 2006 and 2007 results can be classified as statistical fluctuation. We are not looking at possible reasons for this difference.

It is evident that even without combating malicious insiders, and focusing only on preventing accidental data leaks, we can lower the total amount by three quarters, which substantially lowers losses. The prevention of accidental leaks alone saves a significant sum of money, which is sufficient grounds for integrating a prevention system.

Latency

Many data leaks that show up in the media occur during various modes of data transfer, when two or more parties end up blaming each other. Another common occurrence is when a leak is visibile to outsiders. For example, it could be visible to the company’s clients or indexed by search engines. Very few data leaks are reported from within a company, as most companies are keen to hide them. When there are no outside witnesses, this is easier to achieve. In some countries reporting a leak is mandatory, even if no harm is caused. Nevertheless, it is possible to hide a leak.

As such, a significant amount of confidential data leaks go unreported, especially if only one organization is involved. Therefore, the statistics for such events are probably unreliable.

Trends

The following trends have been identified in the ILDP (Information Leakage Detection and Prevention) market:

Lack of standards and a unified approach

It is important to note that despite the fact that many companies offer data leakage prevention software, no single standard for such software has been developed as of yet, neither on the level of legal standards, nor on the level of business practices. There are also no noticeable similarities in the technical demands for ILDP solutions among customers.

Then again, the creation of standards on similar markets (antivirus and antispam protection) took a few years.

Inefficiency of purely technical solutions

Each problem has to be dealt with using the appropriate methods. Since the problem of data leakage is socio-economic, the solution must rely on socio-economic measures. Using technical methods is possible, but only as policy enforcement tools. Solving such a problem with purely technical means is impossible. Each technical solution will have a counter-solution, etc.

In addition to that, the introduction of legal questions complicates things. A person’s privacy is protected in every country. In many countries, such rights are inalienable, meaning there is no way of forfeiting them. Establishing a data leakage prevention system in such a way that it does not conflict with the local laws is difficult. This requires the participation of legal experts, in addition to engineers, from the very beginning of a project.

Despite these problems, most of the solutions on the market are straightforward technical solutions, which result in the basic filtration and monitoring of all traffic that enters and exits the protected network perimeter. Of course, such primitive solutions are easily exploited both by malicious insiders as well as loyal employees. In addition to that, they often lead to a breach of the employee’s constitutional rights and can lead to legal risks for the organization. Purely technical solutions may also antagonize employees or reduce loyalty. Such solutions can cause more harm than they prevent.

Organizational, financial and legal questions can be solved only if leak prevention starts from those areas – when the project is developed by the relevant experts and not by the “tech guys”. The technical side of the question is secondary.

Lack of a Complex Solution

It is important to note that data leakage prevention software developers rarely use a complex approach. Usually the solution protects only one or two data leakage channels, mostly web and email traffic.

Even if controlling one or two channels has some effect against accidental data loss, it is completely useless against malefactors.

Integration and Implementation

At first glance, integrating a data leakage solution into the communication channels and software is beneficial. However, not a single integrated solution is currently available on the market. The closest thing available right now is a software interface for activating preventative software (including data leakage prevention). However, such interfaces are currently rare in firewalls, routers, access points, etc.

However, the developers are actively working on this area. Certain developers have bought ILDP products in order to implement them into general products.

It is unlikely that a fully integrated solution will appear in the next few years. Similar products, such as antivirus and antispam products have not been integrated into email servers and operating systems yet.

Internal IT-threats in Russia in 2007-2008: summary and forecast