Introduction

Virtualization marches victoriously across the globe, adding to its list of champions not only individual IT-specialists and businesses, but even whole sections of the IT industry. In fact, it’s barely possible to find a data center with only physical servers on board: both electricity and physical space are far too expensive nowadays to be used so inefficiently.

Meanwhile, the possibility of hosting multiple servers on a single physical machine is just one benefit among all those offered by virtualization.

Second only to servers, the most important application of today’s virtualization technologies is probably Virtual Desktop Infrastructure, or VDI. While using the same concept of multiple computers hosted inside a single physical ‘body’, its purpose is entirely different from server virtualization: to substitute a heterogeneous and cumbersome ‘zoo’ of physical desktops with homogenous and easily controlled virtual environment.

As opposed to familiar – and age-old – Terminal Services infrastructure, offering shared access to the same machine running a single instance of an operating system, VDI is about ‘genuine’ virtualization. Every single virtualized workstation has its own set of virtual hardware, OS and applications – and its own range of potential security issues. There tends to be a much higher probability, too, of encountering security issues with VDI than with virtualized servers. This is especially true in scenarios which include access to the ‘Big Internet’, with its landscape of threats and hordes of marauding cyber-predators, always hungry for other people’s data and money. And God help you, if you buy into the myth about virtual environments being inherently more secure than physical ones! The exact opposite is true: not only they are similar in terms of threat levels; virtual environments possess some specifics that actually make the task of securing them even more complex.

This is what we are going to talk about here: about VDI myths, specifics – and how to provide proper security for corporate VDI, without compromising any of its many benefits.

VDI: Pros and Cons

The Pros

Before plunging deep into problems associated with VDI, it might be useful to remind ourselves of the benefits that have earned the technology the undying love of both sysadmins and ITSec specialists.

- VDI is effectively agnostic of the end-user’s hardware and software. The only requirement for any client device, be it a regular PC, a smartphone or a thin station, is the ability to run a client application (in some cases, even a simple web browser will do).

- VDI offers a considerably higher level of data security. With all the valuable information stored deep inside the corporate infrastructure or in a datacenter, many data loss scenarios, like device theft or physical loss, are ruled out.

- VDI environments are highly flexible in management terms: every virtualized workstation and application can be deployed and controlled with an ease and speed that’s unattainable for purely physical infrastructures. With finely tuned working practices, it may not even be necessary to solve any problems associated with a given virtual machine: just killing the VM and spawning it back from the template can be enough. All user data can then be re-accessed from centralized storage once the user logs back in.

This list of VDI benefits is clearly incomplete. But even these key points are enough for some businesses requiring high mobility accompanied by strong data security to embrace the concept with eagerness. Typical examples are healthcare, insurance and, in some regions, banking; business processes taking place in these industries are highly regulated and easily formalized, which greatly simplifies the task of VDI implementation.

The Cons

Unfortunately, no solution consists entirely of benefits – and VDI has its range of nuances and limitations to be mindful of.

- VDI is highly sensitive to resource consumption. Virtual environments are designed so that users can perform tasks in a way that’s very similar to using regular PCs. But, even when a limited number of software titles are used for a limited number of tasks, some can not only be resource-hungry, but can have a considerable adverse impact on VDI performance in particular. Few things are more demotivating to a workforce than system lags and general unresponsiveness; as well as unnerving and irritating people, this can easily kill off all the efficiency gains delivered by VDI deployment. So it’s necessary to consider and to constantly monitor all the influences on system responsiveness – including the impact of security solutions.

- VDI works better with formalized business processes. VDI is most easily justified when business processes are predictable, and all the applications used are known. If this is not the case, resource consumption and overall performance calculations can suddenly prove misleading or just plain wrong. The threat to corporate security posed by the unrestricted use of unknown applications, or course, presents a threat to corporate security, as well as compromising the accuracy of performance predictions.

- VDI presents complex requirements for deployed security solutions. As opposed to attacks on data-storing servers and similar scenarios where the main target is remotely accessible data, virtualized workstations are subject to practically the same spectrum of threats as those targeting physical machines. These threats can include, for example, ‘bodiless’ malware using exploits to inject malicious code into legitimate processes and running entirely in the system’s volatile memory. Unfortunately, the majority of well-known specialized solutions claiming to cater for the specific requirements of virtualized environments offer protection at file system level only, which is far from adequate for VDI defense.

Of course, installing a security solution designed for physical desktops, perhaps modified to be ‘virtualization-friendly’, is an option. But this may well result in considerable increases in resource consumption, drastically reducing VDI efficiency. These solutions involve each virtual machine (VM) carrying its own set of engines and databases, each updating independently from its neighbors. In a worst case scenario, a solution’s failure to demonstrate sufficient ‘virtualization awareness’, can result in ‘activity storms’, where multiple simultaneous updates or scanning processes create an avalanche of increased resource consumption, bringing the entire host to a grinding halt.

Myths and Threats

Despite virtual desktops being very similar to their physical counterparts in terms of functionality, the misconception that they are less susceptible to infection is quite widespread amongst users and even IT professionals. Some of the arguments used may look like these:

- Malware itself is afraid of virtual machines, suspecting them of being sandbox systems or researchers’ machines. So, when the malware detects that it’s being launched in a VM, it won’t activate.

- In a properly configured VDI, the VM itself is of no value. If an infection strikes, it’s just a matter of killing off the infected machine, with no need to bother about the malware itself.

Let’s see what stands behind these assertions, and how safe it is to base your approach to VDI security on them.

VM as Malware’s Scarecrow

This argument is based on something that’s actually quite true: many malware specimens do check for signs that they’re being launched inside a VM. But what happens next is not so predictable. Malware creators are keenly aware that these VMs are usually NOT sandboxes and can contain valuable data – or can serve as entry points to entire IT networks. So they’re rapidly learning to tell sandboxes from less sophisticated VMs. For this, an extensive range of indicators can be used: previously investigated IP addresses of researchers’ systems, typical user and computer names, unnecessary system components missing or removed to reduce resource usage – and so on. There are also more advanced tricks and indicators to detect sandboxes, such as leaving some kind of token in the file system or repeated communications with C&C throughout the whole attack cycle (which won’t happen during sandboxing) etc. And there are also directly controlled targeted attacks, during which the command for proceeding (or withdrawing) is issued by living people, based on acquired intelligence.

The bottom line is this: some malware, and only some, may refuse to start in a VM. It would be extremely foolish to rely on this when building a security system for corporate VDI (which is even more susceptible to infection than server VMs).

No machine – no infection?

The main flaw in this argument lies in the perception of the infected machine as an isolated instance. Any infection can involve multiple VMs residing in the same network segment: if just one contracts malware, especially given the lightning-fast speed of a virtualized network, the contagion can spread like wildfire. It doesn’t matter if the original infected machine is killed – the process of cross-infection within a network segment with sufficient vulnerable nodes can theoretically go on forever. Or, more precisely, it can go on until the moment when the whole network segment shuts down entirely.

And another thing. With the initial infected machine consigned to oblivion, traces of the initial infection – all too precious for restoring a full picture of the attack during investigations – will be lost forever.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that some more advanced malware specimens can be remarkably adept at evading detection. Specialized security solutions working only at file system level, without the capability to watch over processes in memory, can give the malware plenty of time to do its job (e.g. syphoning away the data it has found) before the VM is deleted.

Obviously, if the infection is spotted after any malicious files may have been dropped into the file system, mercilessly killing off the affected VM is no guarantee that you have stopped the infection in its tracks.

The Boundless Sea of Threats

We have said that virtual desktops are susceptible to almost the same spectrum of threats as are physical machines. But what about specialized attacks, targeting the specific vulnerabilities of virtualized environments?

Well, there is no shortage of Proof-of-Concept demonstrations, as shown during security conferences and described on the internet. Potentially, such malware could do considerable harm, but… there are as yet no officially registered cases of such attacks being spotted in the wild. Still, there’s no reason to be over-optimistic. The most important driver to innovation in any area – including the creation of malware – is the existence of an obvious demand. Once the penetration rate of virtualized assets reaches a critical point, the in-lab theoretical threat could become a reality in no time. And here we’re talking about the more common threats; if there’s a requirement to attack a particular VDI in order to get to a particularly valuable piece of data (and the money to sponsor such a complex attack)… well, any kind of technology can be put to use, including fully customized designs that are completely unknown to the general public.

Even without the attack scenarios we anticipate in the immediate future, there is enough malware right now to provide VDI owners with the same problems that physical IT network owners already experience.

VDI Defense: Strategy and Tactics

Protecting VDIs is mandatory, and no mythical inherent resilience offers a legitimate defense against the existing threat landscape. So, how do we approach this task appropriately – and what stratagems can be used to best preserve all the beneficial effects of VDI deployment?

Configure Safely!

As we all know, the most dangerous vulnerability in any system is people. And we’re not only talking about careless office staff, mindlessly clicking on links and opening files received from strangers. This also applies to those equally careless IT specialists who configure their systems in ways that leave gaps for intruders to abuse.

So, what screws can be tightened to make the conditions as uncomfortable as possible for any attacker? Here are several examples which, theoretically, are applicable to both physical and virtualized networks.

- Forbid any type of local authorization using domain policies. This can be especially useful for ‘disposable’ VMs, which are created and deleted on demand: the task of fixing a faulty machine, which could require a local login procedure, is not a viable option.

- Whenever the business process allows this, reduce the user’s capability to run unsolicited programs to a minimum, perhaps going as far as deploying a Default Deny scenario. Given the known specifics of particular industries where VDI technology is most popular (like healthcare or insurance), the implementation of such a scenario can be undertaken without much hassle.

- Rule out the use of Java and other command interpreters, including Powershell and even CMD.EXE, if business processes don’t explicitly rely on them. Java remains one of the most exploited components of any system, and script chains are gaining in popularity as a ‘legit’ way of circumventing detection and even application control mechanisms.

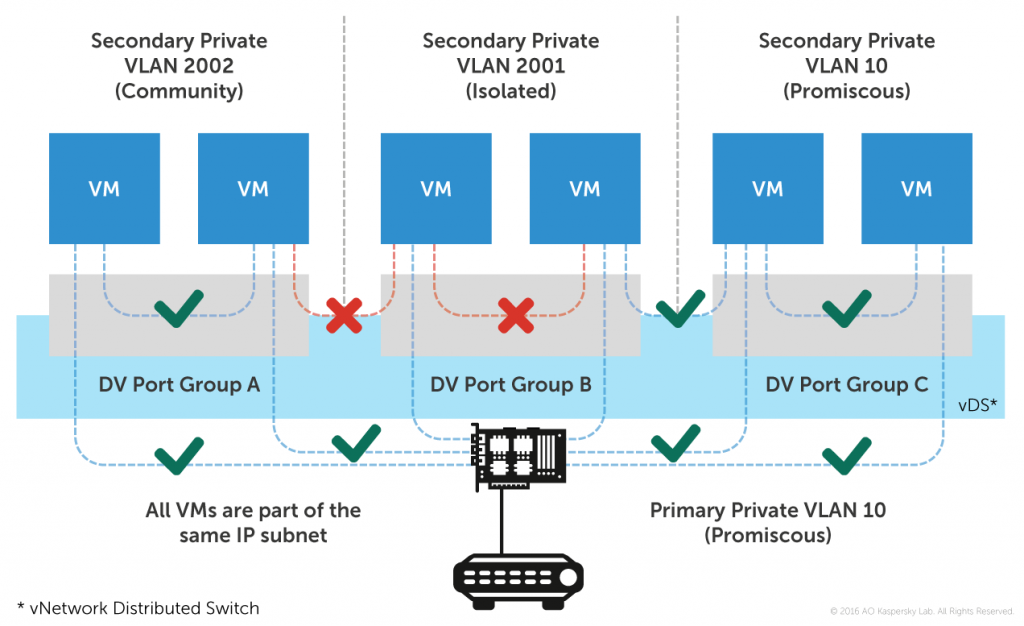

- If the network configuration permits, use Private VLANs to isolate VMs from one another. In the majority of business scenarios, there’s no need for VMs to see one another on the network: they only need access to particular servers and network services – and to the internet if required. Such a configuration can considerably reduce the possibility of infection spreading. Though it’s worth bearing in mind that, in some cases, this would require the physical switchers to support PVLANs as well. But even then, as part of a Software-Defined Networks paradigm, there are virtual switches which prevent the flooding of physical switches without PVLAN support residing in the same IT network.

Private VLANs provide a simple way of selectively isolating VMs without exhausting IP subnets.

Source: VMware

Multi-layered protection

Taking into account the rapidly changing threat landscape, VDI protection should not be in any way inferior to defenses used for regular machines, especially if work undertaken includes accessing the big internet.

This means that, besides traditional signature-based protection or even advanced file-level protection based on heuristic algorithms, any solution should be armed with behavioral detection technologies and some means of exploit mitigation. And this can only be considered a bare minimum; ideally, the solution should possess additional proactive security layers such as application control, web control and device control.

The Conventional Approach

This can readily be achieved by installing regular security solutions using full-weight agents, initially designed for the protection of physical workstations. However, as discussed earlier, even if adjustments have been made to cope with specific aspects of virtual environments, the issue of excessive resource consumption requires a fundamentally different approach.

The Agentless Approach

One such approach leverages VMware’s vShield (and now NSX) technology, and so can only be adopted for VMware based environments. The ‘Agentless’ approach conducts all security activity in a single Security Virtual Machine (or SVM) on the virtual host, using VMware’s own technologies to communicate with and protect the individual VMs.

With signature updates and scanning engines held on just one SVM per host, instead of on every VM that the host is servicing, the resource savings compared with full-agent protection, in terms of both space and processing power, are considerable. And with just one SVM being updated, instead of all those individual machines, traffic is drastically reduced and ‘AV storms’, where lots of machines all try to update or perform malware scanning simultaneously, are eliminated.

For IT environments with no direct external exposure, particularly where foreign agents are not permitted onto clients’ machines – in a data centers for example – the agentless approach is an excellent solution. But, for VDI environments, such as VMware’s own Horizon, where individual machines are so much more exposed, this approach is definitely not sufficient in terms of security. This is primarily because an agentless approach does not allow the security solution any direct access to or control of processes in the individual machine’s memory.

The Lightweight Agent Approach

But there are specialized solutions providing high levels of security AND also operating as an organic element of the virtualized infrastructure, without duplication and resource wastage. The answer lies in solutions using lightweight agents.

Like agentless solutions, this approach also employs a dedicated ‘Security Virtual Machine’ (SVM), which does away with duplicated copies of scanning engines and databases residing on every single protected VM. Instead of relying on the vShield or NSX technology layer, however, this approach employs lightweight program agents, so that the solution can not only reach into the individual VMs’ systems on behalf of the SVM, but can also control processes in the machines’ memory, allowing for behavioral detection by other advanced technologies. And, of course, this approach is not tied to VMware technology, but can be applied to other platforms, including Citrix, Microsoft and KVM.

Solutions built using this principle also allow for the provision of additional security layers.

For example, in our Kaspersky Security for Virtualization | Light Agent, the following technologies are implemented:

- Application Control (powered by cloud-based Dynamic Allowlisting)

- Web Control (with cloud-supported Web Resource Categories)

- Device Control

- Network Attack Blocker (a network IDS/IPS protecting from network-based attacks and exploits)

- HIPS (Host-Based Intrusion Prevention System)

- Firewall (working on multiple OSI levels including Application)

- Anti-phishing (backed by cloud-based reputational service and autonomous heuristics)

(More details about Kaspersky Security for Virtualization | Light Agent can be found here.)

All these protective layers provide much greater levels of security in defense of endpoints which, virtualized or not, remain the primary targets for attackers. Of course, every further security layer requires additional resources, but, with the majority of resource-heavy processes being relocated to the SVM, the deployed lightweight agents can easily remain quite slim.

Such architectures also ensure higher fault tolerance. Should an SVM become unavailable for a period of time, additional security layers won’t leave the machines completely unprotected. In addition, the system event data obtained can be stored locally for later analysis after re-establishing connection with the SVM – or being temporarily rerouted to another SVM on the same network.

Such solutions are initially designed to be fully aware of all virtualization’s unique requirements – and the specifics of VDI in particular, including mechanisms like machine migration or Linked Clones. Properly designed lightweight agents can also be easily embedded into VM templates, allowing instant protection immediately after machine activation.

All these mechanisms and their outcomes and benefits have been tested, in the case of Kaspersky Security for Virtualization | Light Agent, with popular VDI systems including VMware Horizon and Citrix XenDesktop in ‘real life’ conditions.

Heterogeneous environments

Since the connection between the agents and the SVM doesn’t require any platform-dependent intermediate layers, it’s possible not only to protect different virtualization platforms with ease, but also to cover heterogeneous environments with a single solution. This removes the necessity of having different management consoles for each platform solution, and considerably simplifies the management process for IT security specialists, saving time and reducing the probability of human error.

Conclusion

The global transition into virtualized space is still ongoing, and the number of VDI scenarios is growing every day. Even complex, resource-hungry tasks like graphic processing or software development, which were only recently being described as ‘future tech’, are a current reality. Unfortunately, it’s often impossible to formalize complex business processes using strict policies – so there are always ‘soft spots’ in any given system. These soft spots in virtual infrastructure need to be hardened using specialized security solutions combining both traditional and innovative, proactive protection methods. This combination is most commonly found in solutions using lightweight agents – which, given the existing threat model, become a natural choice for VDI protection.

VDI: Non-virtual problems of virtual desktop security, and how to solve them for real

Thomas

try Micro-Segmentation: each VDI gets its own firewall instance at vNIC level. Easiest rule: “from VDI to VDI deny” and all communication between virtual desktops is blocked, including malware. Add Group-Level Firewall Policies to allow only HR group access onto HR application servers and so on.

Bye

Thomas