Introduction

On December 13, 2020, FireEye published a blog post detailing a supply chain attack leveraging Orion IT, an infrastructure monitoring and management platform by SolarWinds. In parallel, Volexity published an article with their analysis of related attacks, attributed to an actor named “Dark Halo”. FireEye did not link this activity to any known actor; instead, they gave it an unknown, temporary moniker – “UNC2452”.

This attack is remarkable from many points of view, including its stealthiness, precision targeting and the custom malware leveraged by the attackers, named “Sunburst” by FireEye.

In a previous blog, we dissected the method used by Sunburst to communicate with its C2 server and the protocol by which victims are upgraded for further exploitation. Similarly, many other security companies published their own analysis of the Sunburst backdoor, various operational details and how to defend against this attack. Yet, besides some media articles, no solid technical papers have been published that could potentially link it to previously known activity.

While looking at the Sunburst backdoor, we discovered several features that overlap with a previously identified backdoor known as Kazuar. Kazuar is a .NET backdoor first reported by Palo Alto in 2017. Palo Alto tentatively linked Kazuar to the Turla APT group, although no solid attribution link has been made public. Our own observations indeed confirm that Kazuar was used together with other Turla tools during multiple breaches in past years.

A number of unusual, shared features between Sunburst and Kazuar include the victim UID generation algorithm, the sleeping algorithm and the extensive usage of the FNV-1a hash.

We describe these similarities in detail below.

For a summary of this analysis and FAQs, feel free to scroll down to “Conclusions“.

We believe it’s important that other researchers around the world investigate these similarities and attempt to discover more facts about Kazuar and the origin of Sunburst, the malware used in the SolarWinds breach. If we consider past experience, looking back to the WannaCry attack, in the early days, there were very few facts linking them to the Lazarus group. In time, more evidence appeared and allowed us, and others, to link them together with high confidence. Further research on this topic can be crucial in connecting the dots.

More information about UNC2452, DarkHalo, Sunburst and Kazuar is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting service. Contact: intelreports[at]kaspersky.com

Technical Details

Background

While looking at the Sunburst backdoor, we discovered several features that overlap with a previously identified backdoor known as Kazuar. Kazuar is a .NET backdoor first reported by Palo Alto in 2017.

Throughout the years, Kazuar has been under constant development. Its developers have been regularly improving it, switching from one obfuscator to another, changing algorithms and updating features. We looked at all versions of Kazuar since 2015, in order to better understand its development timeline.

In the following sections, we look at some of the similarities between Kazuar and Sunburst. First, we will discuss how a particular feature is used in Kazuar, and then we will describe the implementation of the same feature in Sunburst.

Comparison of the sleeping algorithms

Both Kazuar and Sunburst have implemented a delay between connections to a C2 server, likely designed to make the network activity less obvious.

Kazuar

Kazuar calculates the time it sleeps between two C2 server connections as follows: it takes two timestamps, the minimal sleeping time and the maximal sleeping time, and calculates the waiting period with the following formula:

generated_sleeping_time = sleeping_timemin + x (sleeping_timemax - sleeping_timemin)

where x is a random floating-point number ranging from 0 to 1 obtained by calling the NextDouble method, while sleeping_timemin and sleeping_timemax are time periods obtained from the C2 configuration which can be changed with the help of a backdoor command. As a result of the calculations, the generated time will fall in the [sleeping_timemin, sleeping_timemax] range. By default, sleeping_timemin equals two weeks and sleeping_timemax equals four weeks in most samples of Kazuar we analysed. After calculating the sleeping time, it invokes the Sleep method in a loop.

Kazuar implements this algorithm in the following lines of code (class names were omitted from the code for clarity):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 |

long random_multiplication(Random random_0, long long_0) { return (long)(random_0.NextDouble() * (double)long_0); } TimeSpan get_randomized_sleeping_time(Random random_0, TimeSpan timeSpan_0, TimeSpan timeSpan_1) { if (timeSpan_0 > timeSpan_1) { TimeSpan timeSpan = timeSpan_0; timeSpan_0 = timeSpan_1; timeSpan_1 = timeSpan; } long num = random_multiplication(random_0, timeSpan_1.Ticks - timeSpan_0.Ticks); // randomize the sleeping time return new TimeSpan(timeSpan_0.Ticks + num); } TimeSpan get_remaining_time(TimeSpan timeSpan_0, TimeSpan timeSpan_1) { if (!(timeSpan_0 > timeSpan_1)) { return timeSpan_0; } return timeSpan_1; } void wait_between_connections() { for (;;) { // the sleeping loop TimeSpan[] array = get_min_and_max_sleep_time(); /* the previous line retrieves sleeping_time_min and sleeping_time_max from the configuration */ TimeSpan timeSpan = get_randomized_sleeping_time(this.random_number, array[0], array[1]); DateTime last_c2_connection = get_last_c2_connection(); TimeSpan timeSpan2 = DateTime.Now - last_c2_connection; if (timeSpan2 >= timeSpan) { break; /* enough time has passed, the backdoor may connect to the C2 server */ } TimeSpan timeout = get_remaining_time(timeSpan - timeSpan2, this.timespan); // this.timespan equals 1 minute Thread.Sleep(timeout); } } |

Sunburst

Sunburst uses exactly the same formula to calculate sleeping time, relying on NextDouble to generate a random number. It then calls the sleeping function in a loop. The only difference is that the code is somewhat less complex. Below we compare an extract of the sleeping algorithm found in Kazuar and the code discovered in Sunburst.

| Kazuar | Sunburst | ||||

| The listed code is used in multiple versions of the backdoor, including samples with MD5 150D0ADDF65B6524EB92B9762DB6F074 (2016) and 1F70BEF5D79EFBDAC63C9935AA353955 (2019+). The random waiting time generation algorithm and the sleeping loop. |

MD5 2C4A910A1299CDAE2A4E55988A2F102E. The random waiting time generation algorithm and the sleeping loop. |

||||

|

|

Comparing the two code fragments outlined above, we see that the algorithms are similar.

It’s noteworthy that both Kazuar and Sunburst wait for quite a long time before or in-between C2 connections. By default, Kazuar chooses a random sleeping time between two and four weeks, while Sunburst waits from 12 to 14 days. Sunburst, like Kazuar, implements a command which allows the operators to change the waiting time between two C2 connections.

Based on the analysis of the sleeping algorithm, we conclude:

- Kazuar and Sunburst use the same mathematical formula, relying on Random().NextDouble() to calculate the waiting time

- Kazuar randomly selects a sleeping period between two and four weeks between C2 connections

- Sunburst randomly selects a sleeping period between twelve and fourteen days before contacting its C2

- Such long sleep periods in C2 connections are not very common for typical APT malware

- While Kazuar does a Thread.Sleep using a TimeSpan object, Sunburst uses an Int32 value; due to the fact that Int32.MaxValue is limited to roughly 24 days of sleep, the developers “emulate” longer sleeps in a loop to get past this limitation

- In case of both Kazuar and Sunburst, the sleeping time between two connections can be changed with the help of a command sent by the C2 server

The FNV-1a hashing algorithm

Sunburst uses the FNV-1a hashing algorithm extensively throughout its code. This detail initially attracted our attention and we tried to look for other malware that uses the same algorithm. It should be pointed out that the usage of this hashing algorithm is not unique to Kazuar and Sunburst. However, it provides an interesting starting point for finding more similarities. FNV-1a has been widely used by the Kazuar .NET Backdoor since its early versions. We compare the usage of FNV-1a in Kazuar and Sunburst below.

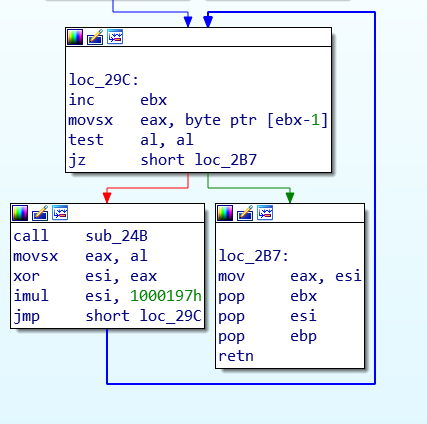

Kazuar

The shellcode used in Kazuar finds addresses of library functions with a variation of the FNV-1a hashing algorithm. The way of finding these addresses is traditional: the shellcode traverses the export address table of a DLL, fetches the name of an API function, hashes it and then compares the hash with a given value.

A variation of the FNV-1a hashing algorithm in Kazuar shellcode present in 2015-autumn 2020 samples, using a 0x1000197 modified constant instead of the default FNV_32_PRIME 0x1000193 (MD5 150D0ADDF65B6524EB92B9762DB6F074)

This customized FNV-1a 32-bit hashing algorithm has been present in the Kazuar shellcode since 2015. For the Kazuar binaries used in 2020, a modified 64-bit FNV-1a appeared in the code:

| Kazuar | ||

| MD5 804785B5ED71AADF9878E7FC4BA4295C (Dec 2020). Implementation of a modified FNV-1a algorithm (64-bit version). |

||

|

We observed that the 64-bit FNV-1a hash present in the 2020 Kazuar sample is also not standard. When the loop with the XOR and multiplication operations finishes execution, the resulting value is XOR-ed with a constant (XOR 0x69294589840FB0E8UL). In the original implementation of the FNV-1a hash, no XOR operation is applied after the loop.

Sunburst

Sunburst uses a modified, 64-bit FNV-1a hash for the purpose of string obfuscation. For example, when started, Sunburst first takes the FNV-1a hash of its process name (solarwinds.businesslayerhost) and checks if it is equal to a hardcoded value (0xEFF8D627F39A2A9DUL). If the hashes do not coincide, the backdoor code will not be executed:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

public static void Initialize() { try { if (OrionImprovementBusinessLayer.GetHash(Process.GetCurrentProcess().ProcessName.ToLower()) == 0xEFF8D627F39A2A9DUL) //"solarwinds.businesslayerhost" { // backdoor execution code } } } |

Hashes are also used to detect security tools running on the system. During its execution Sunburst iterates through the list of processes (Process.GetProcesses()), services (from “SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\services“) and drivers (WMI, “Select * From Win32_SystemDriver“), hashes their names and looks them up in arrays containing the corresponding hardcoded hashes:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

private static bool SearchAssemblies(Process[] processes) { for (int i = 0; i < processes.Length; i++) { ulong hash = OrionImprovementBusinessLayer.GetHash(processes[i].ProcessName.ToLower()); if (Array.IndexOf<ulong>(OrionImprovementBusinessLayer.assemblyTimeStamps, hash) != -1) { return true; } } return false; } |

Below we compare the modified FNV-1a implementations of the two algorithms in Kazuar and Sunburst.

String obfuscation comparison

| Kazuar | Sunburst | ||||

| Code adapted from MD5 804785B5ED71AADF9878E7FC4BA4295C (Dec 2020). Implementation of a modified 64-bit FNV-1a algorithm (deobfuscated, with constant folding applied). | MD5 2C4A910A1299CDAE2A4E55988A2F102E. Implementation of the modified 64-bit FNV-1a algorithm. |

||||

|

|

It should be noted that both Kazuar and Sunburst use a modified 64-bit FNV-1a hash, which adds an extra step after the loop, XOR’ing the final result with a 64-bit constant.

Some readers might assume that the FNV-1a hashing was inserted by the compiler because C# compilers can optimize switch statements with strings into a series of if statements. In this compiler optimized code, the 32-bit FNV-1a algorithm is used to calculate hashes of strings:

| Clean executable | Sunburst | ||||

| Optimized switch statement. | MD5 2C4A910A1299CDAE2A4E55988A2F102E. Switch statement. |

||||

|

|

In the case of Sunburst, the hashes in the switch statement do not appear to be compiler-generated. In fact, the C# compiler uses 32-bit, not 64-bit hashing. The hashing algorithm added by the compiler also does not have an additional XOR operation in the end. The compiler inserts the hashing method in the class, while in Sunburst the same code is implemented within the OrionImprovementBusinessLayer class. The compiler-emitted FNV-1a method will have the ComputeStringHash name. In case of Sunburst, the name of the method is GetHash. Additionally, the compiler inserts a check which compares the hashed string with a hardcoded value in order to eliminate the possibility of a collision. In Sunburst, there are no such string comparisons, which suggests these hash checks are not a compiler optimization.

To conclude the findings, we summarize them as follows:

- Both Sunburst and Kazuar use FNV-1a hashing throughout their code

- A modified 32-bit FNV-1a hashing algorithm has been used by the Kazuar shellcode since 2015 to resolve APIs

- This Kazuar shellcode uses a modified FNV-1a hash where its FNV_32_PRIME is 0x1000197 (instead of the default FNV_32_PRIME 0x1000193)

- A modified 64-bit version of the FNV-1a hashing algorithm was implemented in Kazuar versions found in 2020

- The modified 64-bit FNV-1a hashing algorithms implemented in Kazuar (November and December 2020 variants) have one extra step: after the hash is calculated, it is XORed with a hardcoded constant (0x69294589840FB0E8UL)

- Sunburst also uses a modified 64-bit FNV-1a hashing algorithm, with one extra step: after the hash is calculated, it is XORed with a hardcoded constant (0x5BAC903BA7D81967UL)

- The 64-bit constant used in the last step of the hashing is different between Kazuar and Sunburst

- The aforementioned hashing algorithm is used to conceal plain strings in Sunburst

The algorithm used to generate victim identifiers

Another similarity between Kazuar and Sunburst can be found in the algorithm used to generate the unique victim identifiers, described below.

Kazuar

In order to generate unique strings (across different victims), such as client identifiers, mutexes or file names, Kazuar uses an algorithm which accepts a string as input. To derive a unique string from the given one, the backdoor gets the MD5 hash of the string and then XORs it with a four-byte unique “seed” from the machine. The seed is obtained by fetching the serial number of the volume where the operating system is installed.

Sunburst

An MD5+XOR algorithm can also be found in Sunburst. However, instead of the volume serial number, it uses a different set of information as the machine’s unique seed, hashes it with MD5 then it XORs the two hash halves together. The two implementations are compared in the following table:

| Kazuar | Sunburst | ||||

| The listed code is used in multiple versions of the backdoor, including MD5 150D0ADDF65B6524EB92B9762DB6F074 (2016) and 1F70BEF5D79EFBDAC63C9935AA353955 (2019+). The MD5+XOR algorithm. |

MD5 2C4A910A1299CDAE2A4E55988A2F102E. Part of a function with the MD5+XOR algorithm. | ||||

|

|

To summarize these findings:

- To calculate unique victim UIDs, both Kazuar and Sunburst use a hashing algorithm which is different from their otherwise “favourite” FNV-1a; a combination of MD5+XOR:

- Kazuar XORs a full 128-bit MD5 of a pre-defined string with a four-byte key which contains the volume serial number

- Sunburst computes an MD5 from a larger set of data, which concatenates the first adapter MAC address (retrieved using NetworkInterface.GetAllNetworkInterfaces()), the computer domain (GetIPGlobalProperties().DomainName) and machine GUID (“HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\\SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Cryptography” -> “MachineGuid”) , then it XORs together the two halves into an eight-bytes result

- This MD5+XOR algorithm is present in all Kazuar samples used before November 2020 (a massive code change, almost a complete redesign, was applied to Kazuar in November 2020)

False flags possibility

The possibility of a false flag is particularly interesting and deserves additional attention. In the past, we have seen sophisticated attacks such as OlympicDestroyer confusing the industry and complicating attribution. Subtle mistakes, such as the raw re-use of the Rich header from the Lazarus samples from the Bangladesh bank heist, allowed us to demonstrate that they were indeed false flags and allowed us to eventually connect OlympicDestroyer with Hades, a sophisticated APT group.

Supposing that Kazuar false flags were deliberately introduced into Sunburst, there are two main explanations of how this may have happened:

- The use of XOR operation after the main FNV-1a computation was introduced in the 2020 Kazuar variants after it had appeared in the Sunburst code. In this case, the possibility of a false flag is less likely as the authors of Sunburst couldn’t have predicted the Kazuar’s developers’ actions with such high precision.

- A sample of Kazuar was released before Sunburst was written, containing the modified 64-bit hash function, and went unnoticed by everyone except the Sunburst developers. In this case, the Sunburst developers must have been aware of new Kazuar variants. Obviously, tracing all modifications of unknown code is quite a difficult and tedious task for the following reasons:

- Kazuar’s developers are constantly changing their code as well as the packing methods, thus making it harder to detect the backdoor with YARA rules;

- Kazuar samples (especially the new ones) quite rarely appear on VirusTotal.

The second argument comes with a caveat; the earliest Sunburst sample with the modified algorithm we have seen was compiled in February 2020, while the new Kazuar was compiled in or around November 2020. In the spring and summer of 2020, “old” samples of Kazuar were actively used, without the 64-bit modified FNV-1a hash. This means that option 1 (the extra XOR was introduced in the 2020 Kazuar variants after it had appeared in Sunburst) is more likely.

November 2020 – a new Kazuar

In November 2020, some significant changes happened to Kazuar. On November 18, our products detected a previously unknown Kazuar sample (MD5 9A2750B3E1A22A5B614F6189EC2D67FA). In this sample, the code was refactored, and the malware became much stealthier as most of its code no longer resembled that of the older versions. Here are the most important changes in Kazuar’s code:

- The infamous “Kazuar’s {0} started in process {1} [{2}] as user {3}/{4}.” string was removed from the binary and replaced with a much subtler “Agent started inside {0}.” message, meaning that the backdoor is no longer called Kazuar in the logs. Despite that, the GUID, which was present in Kazuar since 2015 and serves as the backdoor’s unique identifier, still appears in the refactored version of Kazuar.

- Depending on the configuration, the malware may now protect itself from being detected by the Anti-Malware Scan Interface by patching the first bytes of the AmsiScanBuffer API function.

- New spying features have been added to the backdoor. Now Kazuar is equipped with a keylogger and a password stealer which can fetch browser history data, cookies, proxy server credentials and, most importantly, passwords from Internet browsers, Filezilla, Outlook, Git and WinSCP. It also gets vault credentials. The stealer is implemented in the form of a C2 server command.

- Commands have been completely revamped. The system information retrieval function now also hunts for UAC settings and installed hot patches and drivers. The webcam shot-taking command has been completely removed from the backdoor. Commands which allow the execution of WMI commands and the running of arbitrary PowerShell, VBS and JS scripts have been introduced into Kazuar. The malware can now also gather forensic data (“forensic” is a name of a command present in the refactored version of Kazuar). Kazuar collects information about executables that run at startup, recently launched executables and compatibility assistant settings. Furthermore, a command to collect saved credentials from files left from unattended installation and IIS has been introduced into the backdoor.

- The data is now exfiltrated to the C2 server using ZIP archives instead of TAR.

- A class that implements parsing of different file formats has been added into Kazuar. It is currently not used anywhere in the code. This class can throw exceptions with the “Fucking poltergeist” text. In earlier versions of Kazuar, a “Shellcode fucking poltergeist error” message was logged if there was a problem with shellcode.

- The MD5+XOR algorithm is not as widely used as before in the latest version of Kazuar. The backdoor generates most of unique strings and identifiers with an algorithm which is based on the already discussed FNV-1a hash and Base62. The MD5+XOR algorithm itself has been modified. Its new implementation is given below:

Kazuar (2020). The modified MD5+XOR algorithm. 123456789101112131415161718192021222324public static string ZK(string X, string JK = null){if (YU.fG(JK)){JK = oR.d6;}string str = X.ToLower();string s = "pipename-" + str + "-" + JK;byte[] bytes = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(s);byte[] array = MD5.Create().ComputeHash(bytes);byte b = 42;byte b2 = 17;byte b3 = 21;for (int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++){b = (b * b2 & byte.MaxValue);b = (b + b3 & byte.MaxValue);byte[] array2 = array;int num = i;array2[num] ^= b;}Guid guid = new Guid(array);return guid.ToString("B").ToUpper();} - The random sleeping interval generation algorithm mentioned in the main part of the report also appears to be missing from the updated backdoor sample. In order to generate a random sleeping period, the malware now uses a more orthodox random number generation algorithm:

Kazuar (2020). The new random number generation algorithm. Methods were renamed for clarity. 12345678public static long generate_random_number_in_range(long wG, long NG){if (wG > NG){utility_class.swap<long>(ref wG, ref NG);}return Math.Abs(utility_class.get_random_int64()) % (NG - wG + 1L) + wG;}

The newest sample of Kazuar (MD5 024C46493F876FA9005047866BA3ECBD) was detected by our products on December 29. It also contained refactored code.

For now, it’s unclear why the Kazuar developers implemented these massive code changes in November. Some possibilities include:

- It’s a normal evolution of the codebase, where new features are constantly added while older ones are moved

- The Kazuar developers wanted to avoid detection by various antivirus products or EDR solutions

- Suspecting the SolarWinds attack might be discovered, the Kazuar code was changed to resemble the Sunburst backdoor as little as possible

Conclusions

These code overlaps between Kazuar and Sunburst are interesting and represent the first potential identified link to a previously known malware family.

Although the usage of the sleeping algorithm may be too wide, the custom implementation of the FNV-1a hashes and the reuse of the MD5+XOR algorithm in Sunburst are definitely important clues. We should also point out that although similar, the UID calculation subroutine and the FNV-1a hash usage, as well the sleep loop, are still not 100% identical.

Possible explanations for these similarities include:

- Sunburst was developed by the same group as Kazuar

- The Sunburst developers adopted some ideas or code from Kazuar, without having a direct connection (they used Kazuar as an inspiration point)

- Both groups, DarkHalo/UNC2452 and the group using Kazuar, obtained their malware from the same source

- Some of the Kazuar developers moved to another team, taking knowledge and tools with them

- The Sunburst developers introduced these subtle links as a form of false flag, in order to shift blame to another group

At the moment, we do not know which one of these options is true. While Kazuar and Sunburst may be related, the nature of this relation is still not clear. Through further analysis, it is possible that evidence confirming one or several of these points might arise. At the same time, it is also possible that the Sunburst developers were really good at their opsec and didn’t make any mistakes, with this link being an elaborate false flag. In any case, this overlap doesn’t change much for the defenders. Supply chain attacks are some of the most sophisticated types of attacks nowadays and have been successfully used in the past by APT groups such as Winnti/Barium/APT41 and various cybercriminal groups.

To limit exposure to supply chain attacks, we recommend the following:

- Isolate network management software in separate VLANs, monitor them separately from the user networks

- Limit outgoing internet connections from servers or appliances that run third party software

- Implement regular memory dumping and analysis; checking for malicious code running in a decrypted state using a code similarity solution such as Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine (KTAE)

More information about UNC2452, DarkHalo, Sunburst and Kazuar is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting service. Contact: intelreports[at]kaspersky.com

FAQ

- TLDR; just tell us who’s behind the SolarWinds supply chain attack?

Honestly, we don’t know. What we found so far is a couple of code similarities between Sunburst and a malware discovered in 2017, called Kazuar. This malware was first observed around 2015 and is still being used in the wild. The most advanced Kazuar sample we found is from December 2020. During five years of Kazuar evolution, we observed a continuous development, in which significant features, which bear resemblance to Sunburst, were added. While these similarities between Kazuar and Sunburst are notable, there could be a lot of reasons for their existence, including:- Sunburst was developed by the same group as Kazuar

- The Sunburst developers used some ideas or code from Kazuar, without having a direct connection (they used Kazuar code as “inspiration”)

- Both groups, that is, the DarkHalo/UNC2452 and the group using Kazuar obtained their malware from the same source

- One of the Kazuar developers moved to another team, taking his knowledge and tools with them

- The Sunburst developers introduced these subtle links as a form of a false flag, in order to shift the blame to another group

At the moment, we simply do not know which of these options is true. Through further analysis, it is possible that evidence enforcing one or several of these points might arise. To clarify – we are NOT saying that DarkHalo / UNC2452, the group using Sunburst, and Kazuar or Turla are the same.

- What are these similarities? Could these similarities be just coincidences?

In principle, none of these algorithms or implementations are unique. In particular, the things that attracted our attention were the obfuscation of strings through modified FNV-1a algorithms, where the hash result is XOR’ed with a 64-bit constant, the implementation of the C2 connection delay, using a large (and unusual) value (Kazuar uses a random sleeping time between two and four weeks, while Sunburst waits from 12 to 14 days) and the calculation of the victim UID through an MD5 + XOR algorithm. It should be pointed that none of these code fragments are 100% identical. Nevertheless, they are curious coincidences, to say at least. One coincidence wouldn’t be that unusual, two coincidences would definitively raise an eyebrow, while three such coincidences are kind of suspicious to us. - What is this Kazuar malware?

Kazuar is a fully featured .NET backdoor, and was first reported by our colleagues from Palo Alto Networks in 2017. The researchers surmised at the time that it may have been used by the Turla APT group, in order to replace their Carbon platform and other Turla second stage backdoors. Our own observations confirm that Kazuar was used, together with other Turla tools, during multiple breaches in the past few years, and is still in use. Also, Epic Turla resolves imports with another customized version of the FNV-1a hash and has code similarities with Kazuar’s shellcode. - So Sunburst is connected to Turla?

Not necessarily, refer to question 1 for all possible explanations. - The media claims APT29 is responsible for the SolarWinds hack. Are you saying that’s wrong?

We do not know who is behind the SolarWinds hack – we believe attribution is a question better left for law enforcement and judicial institutions. To clarify, our research has identified a number of shared code features between the Sunburst malware and Kazuar.

Our research has placed APT29 as another potential name for “The Dukes”, which appears to be an umbrella group comprising multiple actors and malware families. We initially reported MiniDuke, the earliest malware in this umbrella, in 2013. In 2014, we reported other malware used by “The Dukes”, named CosmicDuke. In CosmicDuke, the debug path strings from the malware seemed to indicate several build environments or groups of “users” of the “Bot Gen Studio”: “NITRO” and “Nemesis Gemina”. In short, we suspect CosmicDuke was being leveraged by up to three different entities, raising the possibility it was shared across groups. One of the interesting observations from our 2014 research was the usage of a webshell by one of the “Bot Gen Studio” / “CosmicDuke” entities that we have seen before in use by Turla. This could suggest that Turla is possibly just one of the several users of the tools under the “Dukes” umbrella. - How is this connected to Cozy Duke?

In 2015, we published futher research on CozyDuke, which seemed to focus on what appeared to be government organizations and commercial entities in the US, Germany and other countries. In 2014, their targets, as reported in the media, included the White House and the US Department of State. At the time, the media also called it “the worst ever” hack. At the moment, we do not see any direct links between the 2015 CozyDuke and the SolarWinds attack. - How solid are the links with Kazuar?

Several code fragments from Sunburst and various generations of Kazuar are quite similar. We should point out that, although similar, these code blocks, such as the UID calculation subroutine and the FNV-1a hashing algorithm usage, as well the sleep loop, are still not 100% identical. Together with certain development choices, these suggest that a kind of a similar thought process went into the development of Kazuar and Sunburst. The Kazuar malware continued to evolve and later 2020 variants are even more similar, in some respect, to the Sunburst branch. Yet, we should emphasise again, they are definitely not identical. - So, are you saying Sunburst is essentially a modified Kazuar?

We are not saying Sunburst is Kazuar, or that it is the work of the Turla APT group. We spotted some interesting similarities between these two malware families and felt the world should know about them. We love to do our part, contributing our findings to the community discussions; others can check these similarities on their own, draw their own conclusions and find more links. What is the most important thing here is to publish interesting findings and encourage others to do more research. We will, of course, continue with our own research too. - Is this the worst cyberattack in history?

Attacks should always be judged from the victim’s point of view. It should also account for physical damage, if any, loss of human lives and so on. For now, it would appear the purpose of this attack was cyberespionage, that is, extraction of sensitive information. By comparison, other infamous attacks, such as NotPetya or WannaCry had a significantly destructive side, with victim losses in the billions of dollars. Yet, for some out there, this may be more devastating than NotPetya or WannaCry; for others, it pales in comparison. - How did we get here?

During the past years, we’ve observed what can be considered a “cyber arms race”. Pretty much all nation states have rushed, since the early 2000s, to develop offensive military capabilities in cyberspace, with little attention to defense. The difference is immediately notable when it comes to the budgets available for the purchase of offensive cyber capabilities vs the development of defensive capabilities. The world needs more balance to the (cyber-)force. Without that, the existing cyber conflicts will continue to escalate, to the detriment of the normal internet user. - Is it possible this is a false flag?

In theory, anything is possible; and we have seen examples of sophisticated false flag attacks, such as the OlympicDestroyer attack. For a full list of possible explanations refer to question 1. - So. Now what?

We believe it’s important that other researchers around the world also investigate these similarities and attempt to discover more facts about Kazuar and the origin of Sunburst, the malware used in the SolarWinds breach. If we consider past experience, for instance looking back to the WannaCry attack, in the early days, there were very few facts linking them to the Lazarus group. In time, more evidence appeared and allowed us, and others, to link them together with high confidence. Further research on this topic can be crucial to connecting the dots.

Indicators of Compromise

File hashes:

E220EAE9F853193AFE77567EA05294C8 (First detected Kazuar sample, compiled in 2015)

150D0ADDF65B6524EB92B9762DB6F074 (Kazuar sample compiled in 2016)

54700C4CA2854858A572290BCD5501D4 (Kazuar sample compiled in 2017)

053DDB3B6E38F9BDBC5FB51FDD44D3AC (Kazuar sample compiled in 2018)

1F70BEF5D79EFBDAC63C9935AA353955 (Kazuar sample compiled in 2019)

9A2750B3E1A22A5B614F6189EC2D67FA (Kazuar sample used in November 2020)

804785B5ED71AADF9878E7FC4BA4295C (Kazuar sample used in December 2020)

024C46493F876FA9005047866BA3ECBD (Most recent Kazuar sample)

2C4A910A1299CDAE2A4E55988A2F102E (Sunburst sample)

More information about UNC2452, DarkHalo, Sunburst and Kazuar is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting service. Contact: intelreports[at]kaspersky.com

Sunburst backdoor – code overlaps with Kazuar

April

Very rigorous report!