More than six years have passed since the banking Trojan Emotet was first detected. During this time it has repeatedly mutated, changed direction, acquired partners, picked up modules, and generally been the cause of high-profile incidents and multimillion-dollar losses. The malware is still in fine fettle, and remains one of the most potent cybersecurity threats out there. The Trojan is distributed through spam, which it sends itself, and can spread over local networks and download other malware.

All its “accomplishments” have been described thoroughly in various publications and reports from companies and independent researchers. This being the case, we decided to summarize and collect in one place everything that is currently known about Emotet.

2014

June

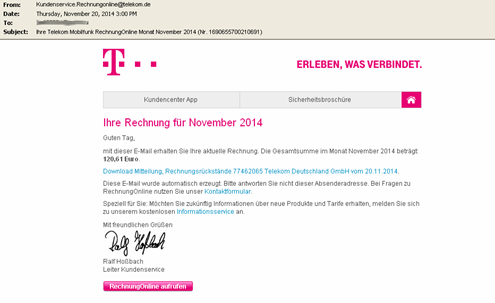

Emotet was first discovered in late June 2014 by TrendMicro. The malware hijacked user banking credentials using the man-in-the-browser technique. Even in those early days, the malware was multicomponent: browser traffic was intercepted by a separate module downloaded from the C&C server. Its configuration file with web injections was also loaded from there. The banker’s main targets were clients of German and Austrian banks, and its main distribution vector was spam disguised as bank emails with malicious attachments or links to a ZIP archive containing an executable file.

Examples of malicious emails with link and attachment

November

In the fall of 2014, we discovered a modification of Emotet with the following components:

- Module for modifying HTTP(S) traffic

- Module for collecting email addresses in Outlook

- Module for stealing accounts in Mail PassView (a password recovery tool)

- Spam module (downloaded additionally as an independent executable file from addresses not linked to C&C)

- Module for organizing DDoS attacks

We came across the latter bundled with other malware, and assume that it was added to Emotet with a cryptor (presumably back then Emotet’s authors did not have their own and so used a third-party one, possibly hacked or stolen). It is entirely possible that the developers were unaware of its presence in their malware. In any event, this module’s C&C centers were not responsive, and it itself was no longer updated (compilation date: October 19, 2014).

In addition, the new modification had begun to employ techniques to steal funds from victims’ bank accounts automatically, using the so-called Automatic Transfer System (ATS). You can read more about this modification in our report.

December

The C&C servers stopped responding and the Trojan’s activity dropped off significantly.

2015

January

In early 2015, a new Emotet modification was released, not all that different from the previous one. Among the changes were: new built-in public RSA key, most strings encrypted, ATS scripts for web injection cleared of comments, targets included clients of Swiss banks.

June

The C&C servers again became unavailable, this time for 18 months. Judging by the configuration file with web injects, the Trojan’s most recent victims were clients of Austrian, German and Polish banks.

2016

December

Emotet redux: for the first time in a long while, a new modification was discovered. This version infected web-surfing victims using the RIG-E and RIG-V exploit kits. This distribution method was not previously used by the Trojan, and, fast-forwarding ahead, would not be employed again. We believe that this was a trial attempt at a new distribution mechanism, which did not pass muster with Emotet’s authors.

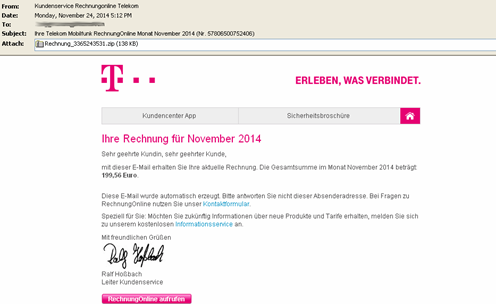

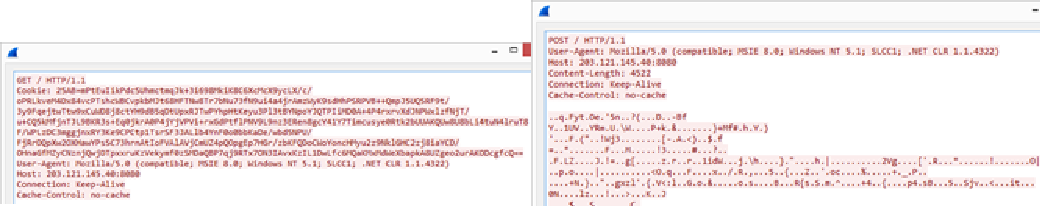

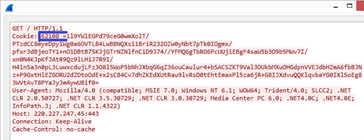

The C&C communication protocol in this modification was also changed: for amounts of data less than 4 KB, a GET request was used, and the data itself was transmitted in the Cookie field of the HTTP header. For larger amounts, a POST request was used. The RC4 encryption algorithm had been replaced by AES, with the protocol itself based on a slightly modified Google Protocol Buffer. In response to the request, the C&C servers returned a header with a 404 Not Found error, which did not prevent them from transmitting the encrypted payload in the body of the reply.

Examples of GET and POST requests used by Emotet

The set of modules sent to the Trojan from C&C was different too:

- Out was the module for intercepting and modifying HTTP(S) traffic

- In was a module for harvesting accounts and passwords from browsers (WebBrowserPassView)

2017

February

Up until now, we had no confirmation that Emotet could send spam independently. A couple of months after the C&C servers kicked back into life, we got proof when a spam module was downloaded from there.

April

In early April, a large amount of spam was seen targeting users in Poland. Emails sent in the name of logistics company DHL asked recipients to download and open a “report” file in JavaScript format. Interestingly, the attackers did not try the further trick of hiding the executable JavaScript as a PDF. The calculation seemed to be that many users would simply not know that JavaScript is not at all a document or report file format.

Example of JS file names used:

dhl__numer__zlecenia___4787769589_____kwi___12___2017.js (MD5:7360d52b67d9fbb41458b3bd21c7f4de)

In April, a similar attack involving fake invoices targeted British-German users.

invoice__924__apr___24___2017___lang___gb___gb924.js (MD5:e91c6653ca434c55d6ebf313a20f12b1)

telekom_2017_04rechnung_60030039794.js (MD5:bcecf036e318d7d844448e4359928b56)

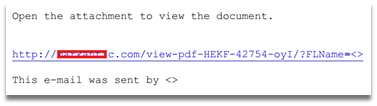

Then in late April, the tactics changed slightly when the spam emails were supplemented with a PDF attachment which, when opened, informed the user that the report in JavaScript format was available for download via the given link.

Document_11861097_NI_NSO___11861097.pdf (MD5: 2735A006F816F4582DACAA4090538F40)

Example of PDF document contents

Document_43571963_NI_NSO___43571963.pdf (MD5: 42d6d07c757cf42c0b180831ef5989cb)

Example of PDF document contents

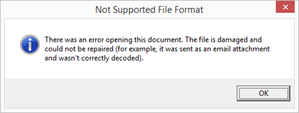

As for the JavaScript file itself, it was a typical Trojan-Downloader that downloaded and ran Emotet. Having successfully infected the system, the script showed the user a pretty error window.

Error message displayed by the malicious JavaScript file

May

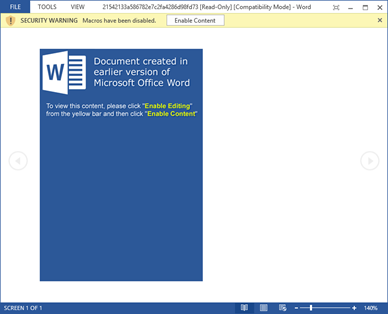

In May, the scheme for distributing Emotet via spam changed slightly. This time, the attachment contained an Office document (or link to it) with an image disguised as an MS Word message saying something about the version of the document being outdated. To open the document, the user was prompted to enable macros. If the victim did so, a malicious macro was executed that launched a PowerShell script that downloaded and ran Emotet.

Screenshot of the opened malicious document ab-58829278.dokument.doc (MD5: 21542133A586782E7C2FA4286D98FD73)

Also in May, it was reported that Emotet was downloading and installing the banking Trojan Qbot (or QakBot). However, we cannot confirm this information: among the more than 1.2 million users attacked by Emotet, Qbot was detected in only a few dozen cases.

June

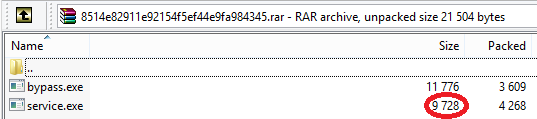

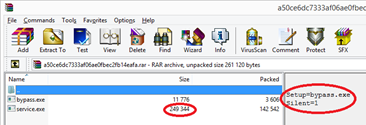

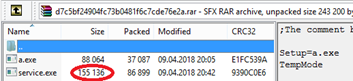

Starting June 1, a tool for spreading malicious code over a local network (Network Spreader), which would later become one of the malware modules, began being distributed from Emotet C&C servers. The malicious app comprised a self-extracting RAR archive containing the files bypass.exe (MD5: 341ce9aaf77030db9a1a5cc8d0382ee1) and service.exe (MD5: ffb1f5c3455b471e870328fd399ae6b8).

Self-extracting RAR archive with bypass.exe and service.exe

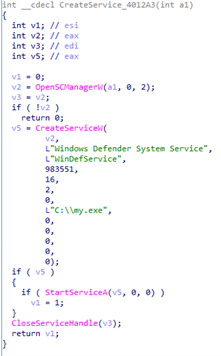

bypass.exe:

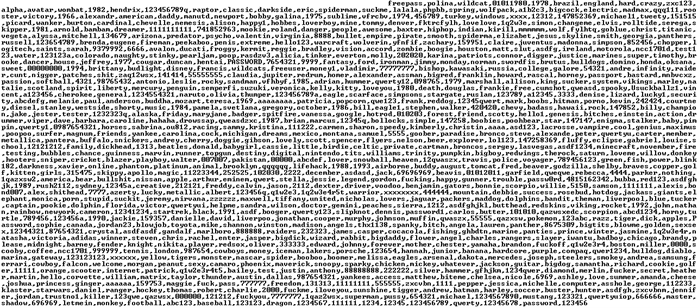

- Searches network resources by brute-forcing passwords using a built-in dictionary

- Copies service.exe to a suitable resource

- Creates a service on the remote system to autorun service.exe

Screenshot of the function for creating the service (bypass.exe)

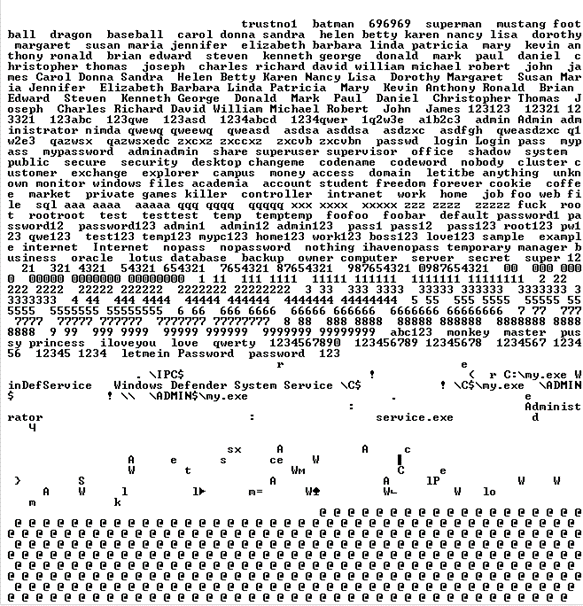

Screenshot with a list of brute-force passwords (bypass.exe)

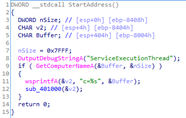

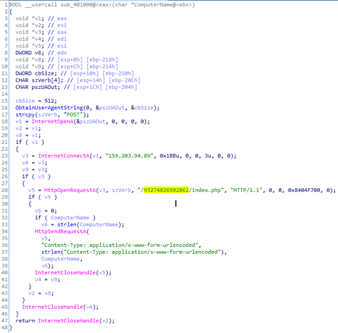

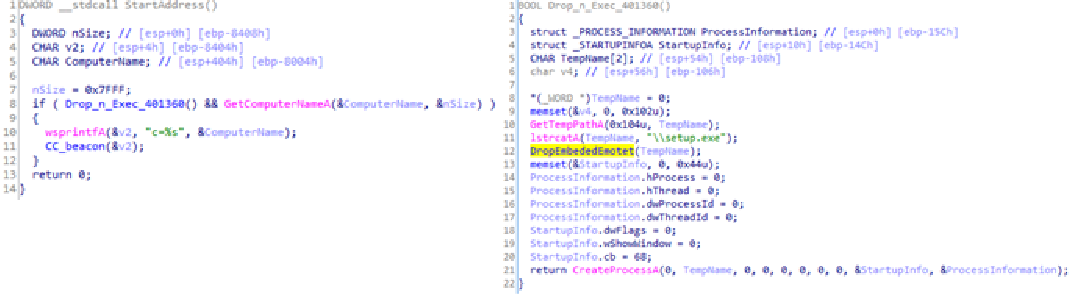

In terms of functionality, service.exe is extremely limited and only sends the name of the computer to the cybercriminals’ server.

Function for generating data to be sent to C&C

Function for sending data to C&C

The mailing was obviously a test version, and the very next day we detected an updated version of the file. The self-extracting archive had been furnished with a script for autorunning bypass.exe (MD5: 5d75bbc6109dddba0c3989d25e41851f), which had not undergone changes, while service.exe (MD5: acc9ba224136fc129a3622d2143f10fb) had grown in size by several dozen times.

Self-extracting RAR archive with bypass.exe and service.exe

The updated service.exe was larger because its body now contained a copy of Emotet. A function was added to save Emotet to disk and run it before sending data about the infected machine to C&C.

New functions in service.exe for saving Emotet to disk and running it

July

An update to the Emotet load module was distributed over the botnet. One notable change: Emotet had dropped GET requests with data transfer in the Cookie field of the HTTP header. Henceforth, all C&C communication used POST (MD5: 643e1f4c5cbaeebc003faee56152f9cb).

August

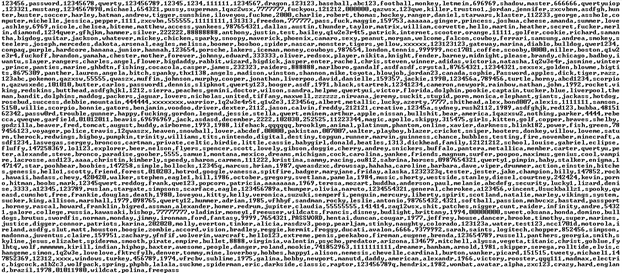

Network Spreader is included in the Emotet “distribution kit” as a DLL (MD5: 9c5c9c4f019c330aadcefbb781caac41), the compilation date of the new module is July 24, 2017, but it was obtained only in August. Recall that it used to be a self-extracting RAR archive with two files: bypass.exe and service.exe. The distribution mechanism did not change much, but the list of brute-force passwords was expanded significantly to exactly 1,000.

Screenshot of the decrypted password list

November

In November 2017, IBM X-Force published a report about the new IcedId banker. According to the researchers, Emotet had been observed spreading it. We got our hands on the first IcedId sample (MD5: 7e8516db16b18f26e504285afe4f0b21) in April, and discovered back then that it was wrapped in a cryptor also used in Emotet. The cryptor was not just similar, but a near byte-for-byte copy of the one in the Emotet sample (MD5: 2cd1ef13ee67f102cb99b258a61eeb20), which was being distributed at the same time.

2018

January

Emotet started distributing the banking Trojan Panda (Zeus Panda, first discovered in 2016 and based on the leaked Zbot banker source code, carries out man-in-the-browser attacks and intercepts keystrokes and input form content on websites).

April

April 9

In early April, Emotet acquired a module for distribution over wireless networks (MD5: 75d65cea0a33d11a2a74c703dbd2ad99), which tried to access Wi-Fi using a dictionary attack. Its code resembled that of the Network Spreader module (bypass.exe), which had been supplemented with Wi-Fi connection capability. If the brute-force was successful, the module transmitted data about the network to C&C.

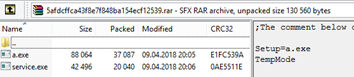

Like bypass.exe, the module was distributed as a separate file (a.exe) inside a self-extracting archive (MD5: 5afdcffca43f8e7f848ba154ecf12539). The archive also contained the above-described service.exe (MD5: 5d6ff5cc8a429b17b5b5dfbf230b2ca4), which, like its first version, could do nothing except send the name of the infected computer to C&C.

Self-extracting RAR archive with a component for distribution over Wi-Fi

The cybercriminals quickly updated the module, and within a few hours of detecting the first version we received an updated self-extracting archive (MD5: d7c5bf24904fc73b0481f6c7cde76e2a) containing a new service.exe with Emotet inside (MD5: 26d21612b676d66b93c51c611fa46773).

Self-extracting RAR archive with updated service.exe

The module was first publicly described only in January 2020, by Binary Defense. The return to the old distribution mechanism and the use of code from old modules looked a little strange, since back in 2017 bypass.exe and service.exe had been merged into one DLL module.

April 14

Emotet again started using GET requests with data transfer in the Cookie field of the HTTP header for data transfer sizes of less than 1 KB simultaneously with POST requests for larger amounts of data. (MD5: 38991b639b2407cbfa2e7c64bb4063c4). Also different was the template for filling the Cookie field. If earlier it took the form Cookie: %X=, now it was Cookie: %u =. The newly added space between the numbers and the equals sign helped to identify Emotet traffic.

Example of a GET request

April 30

The C&C servers suspended their activity and resumed it only on May 16, after which the space in the GET request had gone.

Example of a corrected GET request

June

Yet another banking Trojan started using Emotet to propagate itself. This time it was Trickster (or Trickbot) — a modular banker known since 2016 and the successor to the Dyreza banker.

July

The so-called UPnP module (MD5: 0f1d4dd066c0277f82f74145a7d2c48e), based on the libminiupnpc package, was obtained for the first time. The module enabled port forwarding on the router at the request of a host in the local network. This allowed the attackers not only to gain access to local network computers located behind NAT, but to turn an infected machine into a C&C proxy.

August

In August, there appeared reports of infections by the new Ryuk ransomware — a modification of the Hermes ransomware known since 2017. It later transpired that the chain of infection began with Emotet, which downloaded Trickster, which in turn installed Ryuk. Both Emotet and Trickster by this time had been armed with functions for distribution over a local network, plus Trickster exploited known vulnerabilities in SMB, which further aided the spread of the malware across the local network. Coupled with Ryuk, it made for a killer combination.

At the end of the month, the list of passwords in the Network Spreader module was updated. They still numbered 1,000, but about 100 had been changed (MD5: 3f82c2a733698f501850fdf4f7c00eb7).

Screenshot of the decrypted password list

October

October 12

The C&C servers suspended their activity while we registered no distribution of new modules or updates. Activity resumed only on October 26.

October 30

The data exfiltration module for Outlook (MD5:64C78044D2F6299873881F8B08D40995) was updated. The key innovation was the ability to steal the contents of the message itself. All the same, the amount of stealable data was restricted to 16 KB (larger messages were truncated).

Comparison of the code of the old and new versions of the data exfiltration module for Outlook

November

The C&C servers suspended their activity while we registered no distribution of new modules or updates. Activity resumed only on December 6.

December

More downtime while C&C activity resumed only on January 10, 2019.

2019

March

March 14

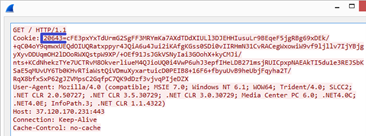

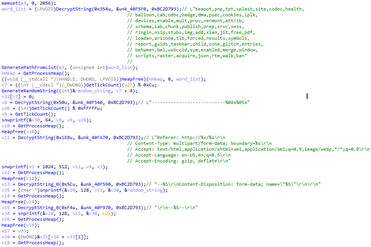

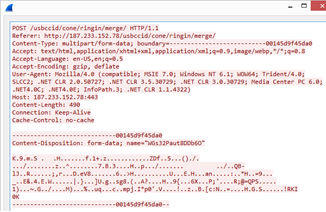

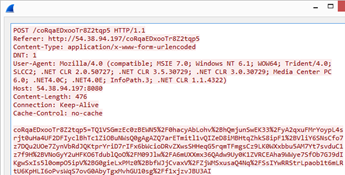

Emotet again modified a part of the HTTP protocol, switching to POST requests and using a dictionary to create the path. The Referer field was now filled, and Content-Type: multipart/form-data appeared. (MD5: beaf5e523e8e3e3fb9dc2a361cda0573)

Code of the POST request generation function

Example of a POST request

March 20

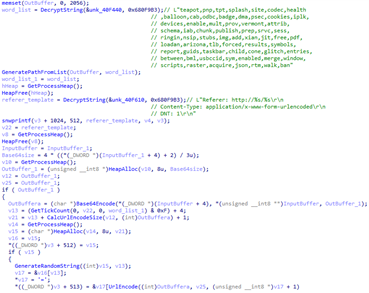

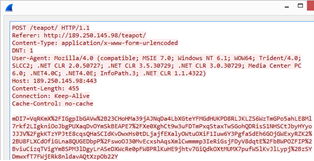

Yet another change in the HTTP part of the protocol. Emotet dropped Content-Type: multipart/form-data. The data itself was encoded using Base64 and UrlEncode (MD5: 98fe402ef2b8aa2ca29c4ed133bbfe90).

Code of the updated POST request generation function

Example of a POST request

April

The first reports appeared that information stolen by the new data exfiltration module for Outlook was being used in Emotet spam mailings: the use of stolen topics, mailing lists and message contents was observed in emails.

May

The C&C servers stopped working for quite some time (three months). Activity resumed only on August 21, 2019. Over the following few weeks, however, the servers only distributed updates and modules with no spam activity being observed. The time was likely spent restoring communication with infected systems, collecting and processing data, and spreading over local networks.

November

A minor change to the HTTP part of the protocol. Emotet dropped the use of a dictionary to create the path, opting for a randomly generated string (MD5: dd33b9e4f928974c72539cd784ce9d20).

Example of a POST request

February

February 6

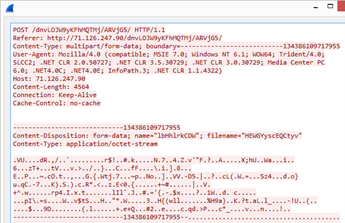

Yet another change in the HTTP part of the protocol. The path now consisted not of a single string, but of several randomly generated words. Content-Type again became multipart/form-data.

Example of a POST request

Along with the HTTP part, the binary part was also updated. The encryption remained the same, but Emotet dropped Google Protocol Buffer and switched to its own format. The compression algorithm also changed, with zlib replaced by liblzf. More details about the new protocol can be found in the Threat Intel and CERT Polska reports.

February 7

C&C activity started to decline and resumed only in July 2020. During this period, the amount of spam fell to zero. At the same time, Binary Defense, in conjunction with various CERTs and the infosec community, began to distribute EmoCrash, a PowerShell script that creates incorrect values for system registry keys used by Emotet. This caused the malware to “crash” during installation. This killswitch worked until August 6, when the actors behind Emotet patched the vulnerability.

July

Only a few days after the resumption of spam activity, online reports appeared that someone was substituting the malicious Emotet payload on compromised sites with images and memes. As a result, clicking the links in spam emails opened an ordinary picture instead of a malicious document. This did not last long, and by July 28 the malicious files had stopped being replaced with images.

Conclusion

Despite its ripe old age, Emotet is constantly evolving and remains one of the most current threats out there. Save for the explosive growth in distribution after five months of inactivity, we have yet to see anything previously unobserved; that said, a detailed analysis always takes time, and we will publish the results of the study in due course. On top of that, we are currently observing the evolution of third-party malware that propagates using Emotet, which we will certainly cover in future reports.

Our security solutions can block Emotet at any stage of attack. The mail filter blocks spam, the heuristic component detects malicious macros and removes them from Office documents, while the behavioral analysis module makes our protection system resistant not only to statistical analysis bypass techniques, but to new modifications of program behavior as well.

To mitigate the risks, it is vital to receive accurate, reliable, before-the-fact information about all information security matters. Scanning IP addresses, file hashes and domains/URLs on opentip can determine if an object poses a genuine threat based on risk levels and additional contextual information. Analyzing files with opentip, using our proprietary technologies, including dynamic, statistical and behavioral analysis, as well as our global reputation system, can help detect advanced mass and latent threats.

And Kaspersky Threat Intelligence is there to track constantly evolving cyberthreats, analyze them, respond to attacks in good time, and minimize the consequences.

IOC

Most active C&Cs in November 2020:

173.212.214.235:7080

167.114.153.111:8080

67.170.250.203:443

121.124.124.40:7080

103.86.49.11:8080

172.91.208.86:80

190.164.104.62:80

201.241.127.190:80

66.76.12.94:8080

190.108.228.27:443

Links to Emotet extracted from malicious documents

hxxp://tudorinvest[.]com/wp-admin/rGtnUb5f/

hxxp://dp-womenbasket[.]com/wp-admin/Li/

hxxp://stylefix[.]co/guillotine-cross/CTRNOQ/

hxxp://ardos.com[.]br/simulador/bPNx/

hxxps://sangbadjamin[.]com/move/r/

hxxps://asimglobaltraders[.]com/baby-rottweiler/duDm64O/

hxxp://sell.smartcrowd[.]ae/wp-admin/CLs6YFp/

hxxps://chromadiverse[.]com/wp-content/OzOlf/

hxxp://rout66motors[.]com/wp-admin/goi7o8/

hxxp://caspertour.asc-florida[.]com/wp-content/gwZbk/

MD5s of malicious Office documents downloading Emotet

59d7ae5463d9d2e1d9e77c94a435a786

7ef93883eac9bf82574ff2a75d04a585

4b393783be7816e76d6ca4b4d8eaa14a

MD5s of Emotet executable files

4c3b6e5b52268bb463e8ebc602593d9e

0ca86e8da55f4176b3ad6692c9949ba4

8d4639aa32f78947ecfb228e1788c02b

28df8461cec000e86c357fdd874b717e

82228264794a033c2e2fc71540cb1a5d

8fc87187ad08d50221abc4c05d7d0258

b30dd0b88c0d10cd96913a7fb9cd05ed

c37c5b64b30f2ddae58b262f2fac87cb

3afb20b335521c871179b230f9a0a1eb

92816647c1d61c75ec3dcd82fecc08b2

The chronicles of Emotet